Public Universal Friend

The Public Universal Friend (born Jemima Wilkinson; November 29, 1752 – July 1, 1819), was born as an English-American to a Quaker family on Rhode Island, and was assigned female at birth. This person suffered a severe illness in 1776 (age 24), and reported having died and been reanimated by the power of God as a genderless evangelist named the Public Universal Friend.

The Friend refused to answer any longer to the previous name, Jemima Wilkinson,[1] quoted Luke 23:3 ("thou sayest it") when visitors asked if it was the name of the person they were addressing, and ignored or chastised those who insisted on using it. The preacher shunned the name "Jemima" completely, having friends hold realty in trust rather than see the name on deeds and titles. Even when a lawyer insisted that the person's Will should identify its subject as having been born under the name Jemima, the preacher refused to sign that name, only making an X which others witnessed, even though the Friend could read and write.[2]

The Friend asked not to be referred to with gendered pronouns. Followers respected these wishes, avoiding gender-specific pronouns even in private diaries, and referring only to "the Public Universal Friend" or short forms such as "the Friend" or "P.U.F."[3]

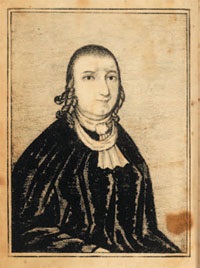

The Friend wore clothes that contemporaries described as androgynous or masculine, chiefly black robes. The Friend preached throughout the northeastern United States, attracting many followers who became the Society of Universal Friends.[4] The Public Universal Friend's theology was broadly similar to that of orthodox Quakers, believing in free will, actively opposing slavery, and supporting sexual abstinence. The Friend persuaded followers who owned slaves to free them. The followers of the Society included people who were black. The Society's followers also included many unmarried women, who took on prominent roles in their communities, which were usually reserved for men.

Further reading

See also

References

- ↑ Moyer, p. 12; Winiarski, p. 430; and Susan Juster, Lisa MacFarlane, A Mighty Baptism: Race, Gender, and the Creation of American Protestantism (1996), p. 27, and p. 28.

- ↑ Catherine A. Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845 (2000), p. 85

- ↑ Juster & MacFarlane, A Mighty Baptism, pp. 27-28; Brekus, p. 85

- ↑ Peg A. Lamphier, Rosanne Welch, Women in American History (2017), p. 331.