History of nonbinary gender: Difference between revisions

imported>Sekhet (→Eighteenth century: Added the earliest written Western description of mahu, a third gender role in Hawai'i and Tahiti.) |

imported>Sekhet |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

* "[[Singular they]]" had already been the standard [[English neutral pronouns|gender-neutral pronoun in English]] for hundreds of years. However, in 1745, prescriptive grammarians began to say that it was no longer acceptable. Their reasoning was that neutral pronouns don't exist in Latin, which was thought to be a better language, so English shouldn't use them, either. They instead began to recommend using "[[English neutral pronouns#He|he]]" as a gender-neutral pronoun.<ref>Maria Bustillos, "Our desperate, 250-year-long search for a gender-neutral pronoun." January 6, 2011. [http://www.theawl.com/2011/01/our-desperate-250-year-long-search-for-a-gender-neutral-pronoun http://www.theawl.com/2011/01/our-desperate-250-year-long-search-for-a-gender-neutral-pronoun]</ref> This started the dispute over the problem of acceptable gender-neutral pronouns in English, which has carried on for centuries now. | * "[[Singular they]]" had already been the standard [[English neutral pronouns|gender-neutral pronoun in English]] for hundreds of years. However, in 1745, prescriptive grammarians began to say that it was no longer acceptable. Their reasoning was that neutral pronouns don't exist in Latin, which was thought to be a better language, so English shouldn't use them, either. They instead began to recommend using "[[English neutral pronouns#He|he]]" as a gender-neutral pronoun.<ref>Maria Bustillos, "Our desperate, 250-year-long search for a gender-neutral pronoun." January 6, 2011. [http://www.theawl.com/2011/01/our-desperate-250-year-long-search-for-a-gender-neutral-pronoun http://www.theawl.com/2011/01/our-desperate-250-year-long-search-for-a-gender-neutral-pronoun]</ref> This started the dispute over the problem of acceptable gender-neutral pronouns in English, which has carried on for centuries now. | ||

* [[Māhū]] ("in the middle") in Kanaka Maoli (Hawaiian) and Maohi (Tahitian) cultures are [[third gender]] persons with traditional spiritual and social roles within the culture. The māhū gender category existed in their cultures during pre-contact times, and still exists today.<ref>Kaua'i Iki, quoted by Andrew Matzner in 'Transgender, queens, mahu, whatever': An Oral History from Hawai'i. Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context Issue 6, August 2001</ref> In the pre-colonial history of Hawai'i, māhū were notable priests and healers, although much of this history was elided through the intervention of missionaries. The first written Western description of māhū occurs in 1789, in Captain William Bligh's logbook of the Bounty, which stopped in Tahiti where he was introduced to a member of a "class of people very common in Otaheitie called Mahoo... who although I was certain was a man, had great marks of effeminacy about him."<ref>William Bligh. Bounty Logbook. Thursday, January 15, 1789.</ref> | * [[Māhū]] ("in the middle") in Kanaka Maoli (Hawaiian) and Maohi (Tahitian) cultures are [[third gender]] persons with traditional spiritual and social roles within the culture. The māhū gender category existed in their cultures during pre-contact times, and still exists today.<ref>Kaua'i Iki, quoted by Andrew Matzner in 'Transgender, queens, mahu, whatever': An Oral History from Hawai'i. Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context Issue 6, August 2001</ref> In the pre-colonial history of Hawai'i, māhū were notable priests and healers, although much of this history was elided through the intervention of missionaries. The first written Western description of māhū occurs in 1789, in Captain William Bligh's logbook of the Bounty, which stopped in Tahiti where he was introduced to a member of a "class of people very common in Otaheitie called Mahoo... who although I was certain was a man, had great marks of effeminacy about him."<ref>William Bligh. Bounty Logbook. Thursday, January 15, 1789.</ref> | ||

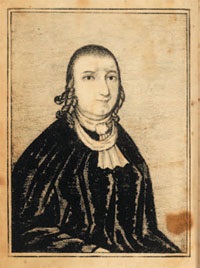

* The [[ | * The [[Public Universal Friend]] (1752 - 1819) was a genderless evangelist who traveled throughout the eastern United States to preach a theology based on that of the Quakers, which was actively against slavery. The Friend believed that God had reanimated them from a severe illness at age 24 with a new spirit, which was genderless. The Friend refused to be called by the birth name,<ref name="Moyer-12 Winiarski-430 Juster-MacFarlane-27-28">Moyer, p. 12; Winiarski, p. 430; and Susan Juster, Lisa MacFarlane, ''A Mighty Baptism: Race, Gender, and the Creation of American Protestantism'' (1996), p. 27, and p. 28.</ref> even on legal documents,<ref name="Brekus-85">Catherine A. Brekus, ''Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845'' (2000), p. 85</ref> and insisted on being called by no pronouns. Followers respected these wishes, avoiding gender-specific pronouns even in private diaries, and referring only to "the Public Universal Friend" or short forms such as "the Friend" or "P.U.F."<ref name="Juster-MacFarlane-27-28 Brekus-85 etc">Juster & MacFarlane, ''A Mighty Baptism'', pp. 27-28; Brekus, p. 85</ref> The Friend wore clothing that contemporaries described as androgynous, which were usually black robes. The Friend's followers came to be known as the Society of Universal Friends, and included people who were black, and many unmarried women who took on masculine roles in their communities.<ref name="Lamphier-Welch-331">Peg A. Lamphier, Rosanne Welch, ''Women in American History'' (2017), p. 331.</ref> | ||

* [[Jens Andersson]] was a nonbinary person in Norway, who married a woman in 1781. It was soon discovered that Andersson had a female body, and the marriage was annulled, while Andersson was accused of sodomy. In the trial, Andersson was asked: "Are you a man or a woman?" It was recorded that the answer was that "he thinks he may be both".[https://skeivtarkiv.no/skeivopedia/et-besynderligt-givtermaal-mellem-tvende-fruentimmer] | * [[Jens Andersson]] was a nonbinary person in Norway, who married a woman in 1781. It was soon discovered that Andersson had a female body, and the marriage was annulled, while Andersson was accused of sodomy. In the trial, Andersson was asked: "Are you a man or a woman?" It was recorded that the answer was that "he thinks he may be both".[https://skeivtarkiv.no/skeivopedia/et-besynderligt-givtermaal-mellem-tvende-fruentimmer] | ||

{{Clear}} | {{Clear}} | ||

Revision as of 05:32, 16 November 2019

This article on the history of nonbinary gender should focus on events directly or indirectly concerning people with nonbinary gender identities. It should not be about LGBT history in general. However, this history will likely need to give dates for a few events about things other than nonbinary gender, such as major events that made more visibility of transgender people in general, gender variant people from early history who may or may not have been what we think of as nonbinary, and laws that concern intersex people that can also have an effect on the legal rights of nonbinary people.

Content warnings: This history may need to talk about some troubling events that could have been traumatic for some readers. Some historical quotes use language that is now seen as offensive.

Tips

Here are some tips for writing respectfully about historical gender variant people whose actual preferred names, pronouns, and gender identities might not be known.

- Dead names. It is disrespectful to call a transgender person by their former name ("dead name") rather than the name that they chose for themself. Some consider their dead name a secret that shouldn't be put in public at all. For living transgender people in particular, this history should show only their chosen names, not their dead names. In this history, some deceased historical transgender persons may have their birth names shown in addition to their chosen names, in cases where it is not known which name they preferred, or where it is otherwise impossible to find information about that person, if one wants to research their history. This should be written in the form of "Chosen Name (née Birth Name)." If history isn't sure which name that person earnestly preferred, write it in the form of "Name, or Other Name."

- Pronouns. It is disrespectful to call a person by pronouns other than those that they ask for. Some historical persons whose preferred pronouns aren't known should be called here by no pronouns. If this isn't possible, they pronouns.

- Words for a person's gender, assigned and otherwise. It is disrespectful to label a person's gender otherwise than they ask for, but it's not always possible to do so. In the case of some historical people, history has recorded how they lived, and what gender they were assigned at birth, but not how they preferred to label their gender identity. For example, it's not known whether certain historical people who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) lived as men because they identified as men (were transgender men), or because it was the only way to have a career in that time and place (and were gender non-conforming cisgender women). This should be mentioned in the more respectful form of, for example, "assigned male at birth (AMAB), lived as a woman," rather than "really a man, passed as a woman." For another example, writing "a military doctor discovered Smith was AFAB" is more respectful than saying "a military doctor discovered Smith was really a woman." For people who lived before the word "transgender" was created, it may be more suitable to call them "gender variant" rather than "transgender." On the other hand, if we have enough information about such a person, we may do best by such people by describing them with the terminology that they most likely would have used for their gender identity if they lived in the present day, with our language.

Wanted events in this time-line

Please help fill out this time-line if you can add information of these kinds:

- Events in the movement for keeping the genders of babies undisclosed.

- Events concerning nonbinary celebrities, and historical persons who clearly stated they were neither female nor male, or both, or androgynes, etc.

- Skim nonbinary blogs looking for past and current historical events.

- Events that show that transgender and especially nonbinary gender identities existed long before the twentieth century.

- Changes in the use of gendered versus gender-neutral language.

Antiquity

- In Mesopotamian mythology, among the earliest written records of humanity, there are references to types of people who are neither male nor female. Sumerian and Akkadian tablets from the 2nd millennium BCE and 1700 BCE describe how the gods created these people, their roles in society, and words for different kinds of them. These included eunuchs, women who couldn't or weren't allowed to have children, men who live as women, intersex people, gay people, and others.[1][2][3]

- Writings from ancient Egypt (Middle Kingdom, 2000-1800 BCE) said there were three genders of humans: males, sekhet (sht), and females, in that order. Sekhet is usually translated as "eunuch," but that's probably an oversimplification of what this gender category means. Since it was given that level of importance, it could potentially be an entire category of gender/sex variance that doesn't fit into male or female. The hieroglyphs for sekhet include a sitting figure that usually means a man. The word doesn't include hieroglyphs that refer to genitals in any way. At the very least, sekhet is likely to mean cisgender gay men, in the sense of not having children, and not necessarily someone who was castrated. [5][6][4]

- Many cultures and ethnic groups have concepts of traditional gender-variant roles, with a history of them going back to antiquity. For example, Hijra and Two-Spirit. These gender identities and roles are often analogous to nonbinary identity, as they don't fit into the Western idea of the gender binary roles.

Eleventh century

- The Anglo-Saxon word wæpen-wifestre, or wæpned-wifestre (Anglo-Saxon, wæpen "sword," "penis," "male" (or wæpned "weaponed," "with a penis," "male") + wif woman, + estre feminine suffix, thus "woman with a weapon," "woman with a penis," or "man woman") was defined in an eleventh-century glossary (Antwerp Plantin-Moretus 32) as meaning "hermaphrodite." The counterpart of this word, wæpned-mann, simply meant "a person armed with a sword" or "male person."[7][8] Wæpen-wifestre is known to be a synonym for "scrat" (intersex).[9] Another synonym given for wæpen-wifestre is bæddel, an which also means intersex, but also feminine men, from which the word "bad" is thought to be derived, due to its use as a slur.[10] The related word bæddling was used in eleventh-century laws for men who had sex with men in a receptive role.[8] Additional meanings of wæpen-wifestre are possible. When wæpen-wifestre is read as "woman with a penis," it could describe a feminine man, a man who has sex with men, or a transgender woman. When read as "woman with a sword," it could refer to a warrior woman. When read as "man woman," it could mean not only an intersex person, but also people who transgressed the gender binary that seems to have been the rule in Anglo-Saxon England, as far as is known from limited literature from that era. From this range of meanings that the word potentially covers, it's possible that wæpen-wifestre may have been a general category for intersex, queer, and gender-variant people in Britain, during the time that was contemporary to Beowulf.

Seventeenth century

- A blog post by the Merriam Webster dictionary editors says, "In the 17th century, English laws concerning inheritance sometimes referred to people who didn’t fit a gender binary using the pronoun it, which, while dehumanizing, was conceived of as being the most grammatically fit answer to gendered pronouns around then."[11] This is an example of people being considered legally outside of male and female. Editors at this wiki would appreciate more information and sources about the laws in question, their dates, and what categories of people they referred to. (Unborn children? Intersex people? People who didn't conform to gender norms?)

- Thomas Hall, who apparently had an equal preference for the birth-name Thomasine (c.1603 – after 1629), was an English servant in colonial Virginia. Hall was raised as a girl, and then presented as a man in order to enter the military.[12] After leaving the military, Hall freely alternated between feminine and masculine attire from one day to the next, until Hall was accused of having sex with both men and women. Whether someone was legally a man or a woman would result in different punishments for that. Several physical examinations disagreed on the details of Hall's sex, and concluded that Hall had been born intersex. Previously, common law required that if a court concluded that someone was intersex, this would result in an injunction that they must live the rest of their life as strictly either male or female, whichever their anatomy resembled the most closely. In this case, the court ruled that "hee is a man and a woeman," and gave the injunction that Hall must from then on wear both masculine and feminine clothing at the same time: "goe clothed in man's apparell, only his head to bee attired in a coyfe and croscloth with an apron before him"[13][14] Intersex is not the same thing as nonbinary, and so an intersex person can identify as male, female, or some other gender. Hall was apparently an intersex person who did not identify strictly as a man or woman, preferred a fluid gender expression, and was then given a legal sex that was both.

Eighteenth century

- "Singular they" had already been the standard gender-neutral pronoun in English for hundreds of years. However, in 1745, prescriptive grammarians began to say that it was no longer acceptable. Their reasoning was that neutral pronouns don't exist in Latin, which was thought to be a better language, so English shouldn't use them, either. They instead began to recommend using "he" as a gender-neutral pronoun.[15] This started the dispute over the problem of acceptable gender-neutral pronouns in English, which has carried on for centuries now.

- Māhū ("in the middle") in Kanaka Maoli (Hawaiian) and Maohi (Tahitian) cultures are third gender persons with traditional spiritual and social roles within the culture. The māhū gender category existed in their cultures during pre-contact times, and still exists today.[16] In the pre-colonial history of Hawai'i, māhū were notable priests and healers, although much of this history was elided through the intervention of missionaries. The first written Western description of māhū occurs in 1789, in Captain William Bligh's logbook of the Bounty, which stopped in Tahiti where he was introduced to a member of a "class of people very common in Otaheitie called Mahoo... who although I was certain was a man, had great marks of effeminacy about him."[17]

- The Public Universal Friend (1752 - 1819) was a genderless evangelist who traveled throughout the eastern United States to preach a theology based on that of the Quakers, which was actively against slavery. The Friend believed that God had reanimated them from a severe illness at age 24 with a new spirit, which was genderless. The Friend refused to be called by the birth name,[18] even on legal documents,[19] and insisted on being called by no pronouns. Followers respected these wishes, avoiding gender-specific pronouns even in private diaries, and referring only to "the Public Universal Friend" or short forms such as "the Friend" or "P.U.F."[20] The Friend wore clothing that contemporaries described as androgynous, which were usually black robes. The Friend's followers came to be known as the Society of Universal Friends, and included people who were black, and many unmarried women who took on masculine roles in their communities.[21]

- Jens Andersson was a nonbinary person in Norway, who married a woman in 1781. It was soon discovered that Andersson had a female body, and the marriage was annulled, while Andersson was accused of sodomy. In the trial, Andersson was asked: "Are you a man or a woman?" It was recorded that the answer was that "he thinks he may be both".[1]

Nineteenth century

- The earliest known true transsexual genital conversion surgery of any kind was performed in 1882 on a trans man named Herman Karl.[22] However, "earliest transsexual genital conversion surgery" depends on one's definition. Eunuchs have been around for all of human history, and while many eunuchs consider themselves cisgender men, many others consider themselves another gender that isn't female or male, such as hijra. Some sources credit the first trans male genital conversion surgery as, instead, the one performed on a trans man named Michael Dillon in the 1930s, perhaps depending on how one defines that surgery.

- Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825-1895) developed a theory in which men who are attracted to men and women who are attracted to women are thus because they are members of a third sex, a mixture of both male and female, and with the psyche or essence of the "opposite" sex, even though their bodies look like cis-gender male and female bodies. The terms "homosexual," "bisexual," and "heterosexual" didn't exist yet, so he coined terms for them all. The overall phenomenon he called Uranismus (in the original German, Urningtum), gay men were uranians (German urnings), lesbians were uraniads (German urningin, as -in is the feminine suffix), whereas heterosexuals were Dionings, so bisexual men were uranodionings, and so on, all of which were distinct from zwitter (intersex). Ulrichs based this naming system on "Plato's Symposium, where two different kinds of love [...are] ruled by two different goddesses of love-- Aphrodite, daughter of Uranus, and Aphrodite, daughter of Zeus and Dione. The second Aphrodite rules those who love the opposite sex." [23] Ulrichs argued that their condition was as natural and healthy as that of what we now call heterosexual people, and he started the movement fighting for their equal legal rights to express their love "between consenting adults, with the free consent of both parties," in his words from 1870, and that they should not be pathologized nor criminalized for doing so.[24]. Although Uranismus was generally addressed in terms of orientation, Ulrichs specifically described various categories of uranians in terms of their gender nonconformity and gender variance. For example, in regard to feminine gay men or queens (who he called Weiblings), Ulrichs wrote in 1879,

"The Weibling is a total mixture of male and female, in which the female element is even predominant, a thoroughly hermaphroditically organized being. Despite his male sexual organs, he is more woman than man. He is a woman with male sexual organs. He is a neutral sex. He is a neuter. He is the hermaphrodite of the ancients."[25]

- Ulrichs goes on to say the direct counterpart of the Weibling among those were were assigned female at birth is "the masculine-inspired, woman-loving Mannlingin," who is equally gender-variant.[25] Ulrichs emphasizes that Uranismus includes gender-variant people, distinct from those who conform from their gender, and also distinct from people born with physical intersex characteristics. As such, Uranismus included people who might today identify as nonbinary.

- Based on Ulrich's work, which were the foundation of Western notions of LGBT people for the next several decades, clinical beliefs around the time of the 1890s "conflat[ed] sex, sexual orientation, and gender expression," thinking of (to use modern words for them) gay, lesbian, transgender, and gender non-conforming people as all having some kind of intersex condition. Such people were said to have "sexual inversion," and were called "inverts."[26]. Another name used for the same category through the 1890s and 1910s was "the intermediate sex," or the "intermediates," which was not physically intersex, and was understood to be often (though not always) gender nonconforming.[27]

- "In 1895, a group of self-described 'androgynes' in New York organized a 'little club called the Cercle Hermaphroditos, based on their self-perceived need 'to unite for defense against the world's bitter persecution.'" This group included people who, in today's words, may have called themselves cross-dressers and transgender people.[28] The group included a nonbinary autobiographer, Jennie June.

- We'wha (1849–1896) was a Zuni Native American from New Mexico, and the most famous lhamana on record. In traditional Zuni culture, the lhamana take on roles and duties associated with both men and women, and they wear a mixture of women's and men's clothing. They work as mediators. As a notable fiber artist, weaver, and potter, We'wha was a prominent cultural ambassador for Native Americans in general, and the Zuni in particular. In 1886, We'wha was part of the Zuni delegation to Washington D.C.. They were hosted by anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson and, during that visit, We'wha met President Grover Cleveland. Friends and relatives alternated masculine and feminine pronouns for We'Wha. We'wha was described as being highly intelligent, having a strong character, and always being kind to children.[29][30]

Twentieth century

- During the 1910s, German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld created the word "transvestite," which at the time meant many more kinds of transgender and even transsexual people. Hirschfeld opened the first clinic to regularly serve them.[31] Hirschfeld's Institute of Sex Research had a library of literature about LGBT people, collected from all over Europe, that couldn't be found anywhere else. This started to bring about a revolution in how society understood and accepted LGBT people, and allowing children to be gender nonconforming. Then, in 1933, the Nazis destroyed it all. This set back LGBT rights for another 40 or so years. The progress wasn't matched again until at least 1990.

- The scholar Jennie June (born 1874) self-identified as a "fairie", "androgyne", "effeminate man", and an "invert", which were contemporary terms for gender and sexual variance. Her transition included changing her full name to Jennie June, and choosing to be castrated, in order to reduce facial hair and sexual desires that disturbed her. June published her first autobiography, The Autobiography of an Androgyne in 1918, and her second The Female-Impersonators in 1922. Her goal in writing her books were to help create an accepting environment for young adults who do not adhere to gender and sexual norms, because that was what she would have wanted for herself, and she wanted to prevent youth from committing suicide.[32] June had formed the Cercle Hermaphroditos in 1895, along with other androgynes who frequented Paresis Hall in New York City. The organization was formed in the hopes "to unite for defense against the world's bitter persecution," and to show that it was natural to be gender and sex variant.[33]

1960s

- Although the earliest known recorded mention of the gender-neutral title Mx was in a magazine article in 1977,[34][35] anecdotes say it was in use as far back as 1965.[36][37]

1970s

- During the 1970s and 1980s, feminists Casey Miller and Kate Swift were significant influences on encouraging people to take up gender inclusive language, as an alternative to sexist language that excludes or dehumanizes women. Some of their books on this are Words and Women (1976) and The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing (1980). They also encoraged the use of gender neutral pronouns.[38] Though their work doesn't directly acknowledge the existence of people outside the gender binary, it did help break down societal views of masculine-as-default, and even the extent of the gender binary in language.

- Up until the 1970s, LGBT people of all kinds largely had a sense of being on the same side together. A major rift started in 1979, when cisgender woman Janice Raymond wrote the book Transsexual Empire, which outlined a transphobic conspiracy theory which told cisgender women to fear trans women. This started the trans-exclusionary movement. As a result, many feminist, lesbian, and women-only spaces became hostile to trans women. This dividing issue made it difficult for feminism to develop an understanding of transgender issues in general. In response, the movement of transgender studies began with an essay by trans woman Sandy Stone in 1987.[39]

1980s

- In the 1980s, the handbook of psychiatry, the DSM-III, included "Gender Identity Disorder" to diagnose people as transsexual.[40] It frames being trans as a strictly pathological mental condition. Getting this diagnosis becomes a necessary step for many trans people to transition. Psychologists during this time believed that a legitimately trans person needed to conform very closely to the gender binary, and even needed to be heterosexual. The psychologists focused on trans women, and isolated them from one another, so they had little community. Meanwhile, trans men got less help from that system, and so they largely left it and formed their own communities.[41]

- In the 1980s and 1990s, Michael Spivak used a set of gender-neutral "E, Emself" pronouns in his math books, in order to avoid indicating a person's gender. The same or similar pronoun had been coined independently by others in prior years. Due to how Spivak popularized these particular pronouns, these soon became known as "spivak pronouns" when they were built into a place where people talked together on the Internet.[42]

1990s

- In 1990, the Native American/First Nations gay and lesbian conference chooses Two-Spirit as a better English umbrella term for some gender identities unique to Native American cultures, many of which can be considered as outside of the Western gender binary.[43]

- In 1994, Kate Bornstein, who currently identifies as nonbinary,[44] published the book Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women, and the Rest of Us, about her experience as a transgender person identifying outside of the gender binary.

- In 1995, a neutrois person named H. A. Burnham creates the word "neutrois," a name for a nonbinary gender identity.[45]

- The earliest known use of the word "genderqueer" is by Riki Anne Wilchins in the Spring 1995 newsletter of Transexual Menace. In 1995 she was published in the newsletter In Your Face, where she used the term genderqueer.[46] In the newsletter, the term appears to refer to people with complex or unnamed gender expressions. Wilchins stated she identifies as genderqueer in her 1997 autobiography.[47]

- In the late 1990s, people in Japan who identified as neither male nor female began calling themselves X-gender.

Twenty-first century

2000s

- Australian Alex MacFarlane believed to be the first person in Australia to obtain a birth certificate recording sex as indeterminate, and the first Australian passport with an "X" sex marker. Australia began to let people mark their gender as "X" on their birth certificates and passports.[48][49]

- In 2009, India began to allow voters outside the gender binary to "register their gender as 'other' on ballots submitted to the Election Commission."[50]

2010s

2011

2013

- A newer version of the handbook of psychiatry, the DSM-5, replaces the "gender identity disorder" diagnosis with "gender dysphoria," to lessen the pathologization of transgender people.[53]

2014

- The Supreme Court of India ruled in favor of rights and legal recognition of "Indians who identify as neither male nor female, or those who identify as transgender women, known as hijra."[50]

- The social networking site Facebook began to let users to choose from 50 gender options.

- The transgender community on the social networking site Tumblr created hundreds of nounself pronouns.

2015

- Nepal began to allow X gender passports.[54]

- Dictionary.com put in the nonbinary gender words agender, bigender, and genderfluid.[55] Meanwhile, the Oxford English Dictionary announced that it might add the title Mx.[56][57]

- One of Irish broadcaster RTE’s best-known journalists, Jonathan Rachel Clynch, came out as genderfluid.[58]

- Singer, songwriter, and actor Miley Cyrus explained she didn't relate to being a girl or a boy.[59]

2016

- In the USA, the states of Oregon and then California began to allow for a nonbinary legal gender, though getting this recognized on identity documents (driver's licenses and passports) is another matter. California began to allow nonbinary driver's licenses.[60]

Further reading

- Wikipedia: Timeline of LGBT history

- Wikipedia: History of transgenderism in the United States

- Wikipedia: Timeline of intersex history

- Wikipedia: Intersex in history

References

- ↑ Murray, Stephen O., and Roscoe, Will (1997). Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History, and Literature. New York: New York University Press.

- ↑ Nissinen, Martti (1998). Homoeroticism in the Biblical World, Translated by Kirsi Stjedna. Fortress Press (November 1998) p. 30. ISBN|0-8006-2985-X

See also: Maul, S. M. (1992). Kurgarrû und assinnu und ihr Stand in der babylonischen Gesellschaft. Pp. 159–71 in Aussenseiter und Randgruppen. Konstanze Althistorische Vorträge und Forschungern 32. Edited by V. Haas. Konstanz: Universitätsverlag. - ↑ Leick, Gwendolyn (1994). Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature. Routledge. New York.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mark Brustman. "The Third Gender in Ancient Egypt." "Born Eunuchs" Home Page and Library. 1999. https://people.well.com/user/aquarius/egypt.htm

- ↑ Sethe, Kurt, (1926), Die Aechtung feindlicher Fürsten, Völker und Dinge auf altägyptischen Tongefäßscherben des mittleren Reiches, in: Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, 1926, p. 61.

- ↑ Sandra Stewart. "Egyptian third gender." http://www.gendertree.com/Egyptian%20third%20gender.htm

- ↑ Dana Oswald, Monsters, Gender and Sexuality in Medieval English Literature. Rochester, NY: D.S. Brewer, 2010. p. 93.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 David Clark. Between medieval men: Male friendship and desire in early medieval English literature. Oxford University Press, 2009. P. 63-65.

- ↑ Catholicon Anglicum: An English-Latin Word-book, dated 1483, volume 30. Accessed via Google Books: https://books.google.com/books?id=I7wKAAAAYAAJ&dq=%22W%C3%A6pen-wifestre%22&pg=PA325#v=onepage&q=%22W%C3%A6pen-wifestre%22&f=false

- ↑ "bad (adj.)" Online Etymology Dictionary. https://www.etymonline.com/word/bad

- ↑ “Words We’re Watching: Singular 'They:' Though singular 'they' is old, 'they' as a nonbinary pronoun is new—and useful.” Merriam Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/singular-nonbinary-they Captured November 2017.

- ↑ Norton, Mary Beth, "Communal Definitions of Gendered Identity in Colonial America", Ronald Hoffman, Mechal Sobel, Fredrika J. Teute (eds) Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America (University of North Carolina Press, 1997), pp. 40ff.

- ↑ Floyd, Don (2010). The Captain and Thomasine. Raleigh, NC: Lulu Enterprises. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-557-37676-6.

- ↑ Reis, Elizabeth (September 2005). "Impossible Hermaphrodites: Intersex in America, 1620–1960". The Journal of American History: 411–441.

- ↑ Maria Bustillos, "Our desperate, 250-year-long search for a gender-neutral pronoun." January 6, 2011. http://www.theawl.com/2011/01/our-desperate-250-year-long-search-for-a-gender-neutral-pronoun

- ↑ Kaua'i Iki, quoted by Andrew Matzner in 'Transgender, queens, mahu, whatever': An Oral History from Hawai'i. Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context Issue 6, August 2001

- ↑ William Bligh. Bounty Logbook. Thursday, January 15, 1789.

- ↑ Moyer, p. 12; Winiarski, p. 430; and Susan Juster, Lisa MacFarlane, A Mighty Baptism: Race, Gender, and the Creation of American Protestantism (1996), p. 27, and p. 28.

- ↑ Catherine A. Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845 (2000), p. 85

- ↑ Juster & MacFarlane, A Mighty Baptism, pp. 27-28; Brekus, p. 85

- ↑ Peg A. Lamphier, Rosanne Welch, Women in American History (2017), p. 331.

- ↑ James Sears, Gay, Lesbian and Transgender Issues in Education. p. 109. Google Books link

- ↑ We are everywhere: A historical sourcebook of gay and lesbian politics. P. 61. https://books.google.com/books?id=rDG3xdtDutkC&lpg=PA64&dq=urning&pg=PA65#v=onepage&q=urning&f=false

- ↑ Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, "Araxes: Appeal for the liberation of the urning's nature from penal law." 1870. Excerpt reprinted in: We are everywhere: A historical sourcebook of gay and lesbian politics. P. 63-65. https://books.google.com/books?id=rDG3xdtDutkC&lpg=PA64&dq=urning&pg=PA65#v=onepage&q=urning&f=false

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, "Critical arrow." 1879. Excerpt reprinted in: We are everywhere: A historical sourcebook of gay and lesbian politics. P. 64-65. https://books.google.com/books?id=rDG3xdtDutkC&lpg=PA64&dq=urning&pg=PA65#v=onepage&q=urning&f=false

- ↑ "What's the history behind the intersex rights movement?" Intersex Society of North America. http://www.isna.org/faq/history

- ↑ Edward Carpenter. "The intermediate sex." Love's Coming-of-Age. 1906. Accessed via the archive in Sacred Texts at http://www.sacred-texts.com/lgbt/lca/lca09.htm

- ↑ Susan Stryker, "Why the T in LGBT is here to stay." Salon. October 11, 2007. http://www.salon.com/2007/10/11/transgender_2/

- ↑ Matilda Coxe Stevenson, The Zuni Indians: Their Mythology, Esoteric Fraternities, and Ceremonies, (BiblioBazaar, 2010) p. 37

- ↑ Suzanne Bost, Mulattas and Mestizas: Representing Mixed Identities in the Americas, 1850-2000, (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2003, pg.139

- ↑ Trans Health editors, “Timeline of gender identity research.” 2002-04-23. http://www.trans-health.com/2002/timeline-of-gender-identity-research

- ↑ Meyerowitz, J. "Thinking Sex With An Androgyne". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 17.1 (2010): 97–105. Web. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ↑ Katz, Jonathan Ned. "Transgender Memoir of 1921 Found". Humanities and Social Sciences Online. N.p., 10 October 2010. Web. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ↑ Practical Androgyny (PractiAndrogyny). May 4, 2015. https://twitter.com/PractiAndrogyny/status/595329679789260801

- ↑ The Single Parent, vol 20. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IgwdAQAAMAAJ&dq=editions%3ALCCNsc83001271&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=Mx

- ↑ Cassian Lotte Lodge (cassolotl). "Mx has been around since the 1960s." November 26, 2014. Blog post. http://cassolotl.tumblr.com/post/103645470405

- ↑ octopus8. November 18, 2014. Comment on news article. http://www.theguardian.com/world/shortcuts/2014/nov/17/rbs-bank-that-likes-to-say-mx#comment-43834815

- ↑ Elizabeth Isele, "Casey Miller and Kate Swift: Women who dared to disturb the lexicon." http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/old-WILLA/fall94/h2-isele.html

- ↑ "History of transgenderism in the United States." Wikipedia. Retrieved November 29, 2014. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_transgenderism_in_the_United_States

- ↑ Trans Health editors, “Timeline of gender identity research.” 2002-04-23. http://www.trans-health.com/2002/timeline-of-gender-identity-research

- ↑ fakecisgirl, "The Misery Pimps: The People Who Impede Trans Liberation." October 7, 2013. Fake Cis Girl (personal blog). https://fakecisgirl.wordpress.com/2013/10/07/the-misery-pimps-the-people-who-impede-trans-liberation/

- ↑ "Gender-neutral pronoun FAQ." https://web.archive.org/web/20120229202924/http://aetherlumina.com/gnp/listing.html

- ↑ "Two-Spirit." Wikipedia. Retrieved November 29, 2014. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-Spirit

- ↑ https://www.slantmagazine.com/house/article/pretty-damn-bowie-kate-bornstein-on-their-broadway-debut-in-straight-white-men

- ↑ Axey, Qwill, Rave, and Luscious Daniel, eds. “FAQ.” Neutrois Outpost. Last updated 2000-11-23. Retrieved 2001-03-07. http://web.archive.org/web/20010307115554/http://www.neutrois.com/faq.htm

- ↑ Collection: In Your Face / Subject: Riki Anne Wilchins - Digital Transgender Archive Search Results https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/catalog?f%5Bcollection_name_ssim%5D%5B%5D=In+Your+Face&f%5Bdta_other_subject_ssim%5D%5B%5D=Riki+Anne+Wilchins

- ↑ Genderqueer History http://genderqueerid.com/gqhistory

- ↑ "X marks the spot for intersex Alex" Archived 2013-11-11 at WebCite, West Australian, via bodieslikeours.org. 11 January 2003 https://www.webcitation.org/6L2hqf44G?url=http://www.bodieslikeours.org/pdf/xmarks.pdf

- ↑ Holme, Ingrid (2008). "Hearing People's Own Stories". Science as Culture. 17 (3): 341–344. doi:10.1080/09505430802280784. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09505430802280784

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Sunnivie Brydum. "Indian Supreme Court Recognizes Third Gender." April 15, 2014. Advocate. https://www.advocate.com/world/2014/04/15/indian-supreme-court-recognizes-third-gender

- ↑ http://www.attn.com/stories/868/transgender-passport-status

- ↑ Tristin Hopper, "Genderless passports ‘under review’ in Canada." May 8, 2012. National Post. http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/genderless-passports-under-review-in-canada

- ↑ "History of transgenderism in the United States." Wikipedia. Retrieved November 29, 2014. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_transgenderism_in_the_United_States

- ↑ Clarissa-Jan Lim. "New 'Third Gender' Option on Nepal Passports Finally Protects the Rights of LGBT Community." Bustle. January 8, 2015. http://www.bustle.com/articles/57466-new-third-gender-option-on-nepal-passports-finally-protects-the-rights-of-lgbt-community

- ↑ "New words added to Dictionary.com." May 6, 2015. Dictionary.com. http://blog.dictionary.com/2015-new-words/

- ↑ Loulla-Mae Eleftheriou-Smith, "Gender neutral honorific Mx 'to be included' in the Oxford English Dictionary alongside Mr, Ms and Mrs and Miss." May 3, 2015. The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/gender-neutral-honorific-mx-to-be-included-in-the-oxford-english-dictionary-alongside-mr-ms-and-mrs-and-miss-10222287.html

- ↑ Mary Papenfuss, "Oxford Dictionary may include gender-neutral honorific 'Mx'." May 5, 2015. International Business Times. http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/oxford-dictionary-may-include-gender-neutral-honorific-mx-1499626

- ↑ Tom Sykes, "A ‘Gender Fluid’ Journalist Comes Out To Irish Cheers." 2015-09-18. Daily Beast. http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/09/18/a-gender-fluid-journalist-comes-out-to-irish-cheers.html

- ↑ Exclusive: Miley Cyrus Launches Anti-Homelessness, Pro-LGBT ‘Happy Hippie Foundation’, out.com, May 5, 2015

- ↑ Mary Emily O'Hara. "Californian Becomes Second US Citizen Granted 'Non-Binary' Gender Status." NBC News. Sept. 26, 2016. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/californian-becomes-second-us-citizen-granted-non-binary-gender-status-n654611