Public Universal Friend

The Public Universal Friend (born Jemima Wilkinson; November 29, 1752 – July 1, 1819), was born as an English-American to a Quaker family on Rhode Island, and was assigned female at birth. This person suffered a severe illness in 1776 (age 24), and reported having died and been reanimated by the power of God as a genderless evangelist named the Public Universal Friend.

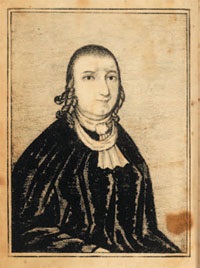

A portrait of the Public Universal Friend (in black clerical robes and white cravat) from the biography written by David Hudson in 1821.[1] | |

| Date of birth | November 29, 1752[2][3] |

|---|---|

| Place of birth | Cumberland, Rhode Island |

| Date of death | July 1, 1819[4] |

| Nationality | American |

| Pronouns | No pronouns |

| Gender identity | genderless |

The Friend refused to answer to the previous name any longer,[5] quoted Luke 23:3 ("thou sayest it") when visitors asked if it was the name of the person they were addressing, and ignored or chastised those who insisted on using it. The preacher shunned the name completely, having friends hold realty in trust rather than see the name on deeds and titles. Even when a lawyer insisted that the person's Will should identify its subject as having been born under the name Jemima, the preacher refused to sign that name, only making an X which others witnessed, despite being able to read and write.[6]

The Friend asked not to be referred to with gendered pronouns. Followers respected these wishes, largely avoiding gender-specific pronouns even in private diaries, and referring only to "the Public Universal Friend" or short forms such as "the Friend" or "P.U.F."[7] The Friend wore clothes that contemporaries described as androgynous or masculine, chiefly black robes. When a man criticized this manner of dress, saying "the singularity of [your] appearance would excited many remarks" including "some indecent ones", the preacher replied "there is nothing indecent or improper in my dress or appearance; I am not accountable to mortals, I am that I am",[8][9] saying the same thing ("I am that I am") when someone asked if the Friend was male or female.[10][11] Followers considered the Friend's androgynous clothing consistent with the evangelist's genderless spirit, and Susan Juster and other writers speculate that, for followers, the Friend embodied Paul's statement in Galatians 3:28 that "there is neither male nor female" in Christ.[12][13]

The Friend preached throughout the northeastern United States, attracting many followers who became the Society of Universal Friends.[14] The Friend's theology was broadly similar to that of other Quakers, believing in free will, actively opposing slavery, and supporting sexual abstinence. The Friend persuaded followers who owned people in slavery to free them, and the Society included black people. The Society also included many unmarried women, who took prominent roles in their communities that were usually reserved for men. In the 1790s, the Society formed the town of Jerusalem, New York, near Penn Yan. Many modern writers have portrayed the Friend as a pioneering figure in the history of women's rights (like Juster), sometimes even while acknowledging that the Friend defied the idea of gender as binary and as essential or innate (like Catherine Brekus and Catherine Wessinger),[15] or else in transgender history (like Scott Larson and Rachel Hope Cleves).[13][16] Historian Michael Bronski calls the Friend as an instance of an early American publicly identifying as non-binary.[11]

Further reading

See also

References

- ↑ David Hudson, History of Jemima Wilkinson: A Preacheress of the Eighteenth Century (1821, S. P. Hull).

- ↑ Herbert Wisbey, Jr., Pioneer Prophetess: Jemima Wilkinson, the Publick Universal Friend (2009 [1964], Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-7551-1), p. 3.

- ↑ Paul B. Moyer, The Public Universal Friend: Jemima Wilkinson and Religious Enthusiasm in Revolutionary America (2015, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-5413-4), p. 13.

- ↑ Wisbey, p. 163; Moyer, p. 243.

- ↑ Moyer, p. 12; Winiarski, p. 430; and Susan Juster, Lisa MacFarlane, A Mighty Baptism: Race, Gender, and the Creation of American Protestantism (1996), p. 27, and p. 28.

- ↑ Catherine A. Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845 (2000), p. 85

- ↑ Juster & MacFarlane, A Mighty Baptism, pp. 27-28; Brekus, p. 85

- ↑ Susan Juster, Doomsayers: Anglo-American Prophecy in the Age of Revolution (2010, ISBN 978-0-8122-1951-7, p. 228

- ↑ Adam Jortner, Blood from the Sky: Miracles and Politics in the Early American Republic (2017), p. 192

- ↑ Moyer (2015), p. 24

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Samantha Schmidt, A genderless prophet drew hundreds of followers long before the age of nonbinary pronouns, January 5, 2020, The Washington Post.

- ↑ Juster, p. 373; also Charles Campbell, 1 Corinthians: Belief (2018, ISBN 1611648432).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Scott Larson, "Indescribable Being": Theological Performances of Genderlessness in the Society of the Publick Universal Friend, 1776–1819, Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal (University of Pennsylvania Press), volume 12, number 3, Fall 2014, pp. 576–600

- ↑ Peg A. Lamphier, Rosanne Welch, Women in American History (2017, ISBN 1610696034), p. 331.

- ↑ Catherine Wessinger, The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism (2016, Template:ISBN), p. 173; Brekus (2000), p. 90; Betcher, p. 77.

- ↑ Rachel Hope Cleves, Beyond the Binaries in Early America: Special Issue Introduction, Early American Studies 12.3 (2014), pp. 459–468; also The Routledge History of Queer America, edited by Don Romesburg (2018, Template:ISBN), esp. § "Revolution's End".