Uranian

| |

| ||||||

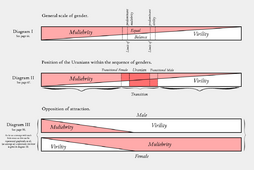

Uranian, or Urning, was a term used during the 19th and early-20th Centuries referring to gender and sexual identities, originally divided into separate sub-classifications, with Mannling Uranians generally describing effeminate homosexual men, and Weibling Uranians being used to describe people, who were not assigned female at birth, who identify and express themselves as female.[2]

Although this distinction originally existed, by the early-20th century the original sub-classifications of the term were rarely used, and Uranian on its own had broadened into an umbrella term for effeminate, homosexual men, third gender people, nonbinary people, among others.

In Karl Heinrich Ulrichs' work where he first uses the term Urning (a German word from which the English "Uranian" is said to have derived), the separate term Urningin was proposed for homosexual, assigned female at birth people who identify and express themselves in a generally-masculine way.[3] Urningin was rarely used however, and its meaning was (by the early-20th century) generally considered to fall within the range of meanings of Uranian on its own.

By the 1920s or 1930s, the term Uranian had fallen out of common usage, most likely due to the lack of definition and general impreciseness it had acquired during the decades prior.

Terminology

Uranian is believed to be an English adaptation of the German word Urning, which was first published by activist Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825–95) in a series of five booklets (1864–65) that were collected under the title Forschungen über das Räthsel der mannmännlichen Liebe ("Research into the Riddle of Man-Male Love"). Ulrich developed his terminology before the first public use of the term "homosexual", which appeared in 1869 in a pamphlet published anonymously by Karl-Maria Kertbeny (1824–82).

The word Uranian (Urning) was derived by Ulrichs from the Greek goddess Aphrodite Urania, who was created out of the god Uranus' testicles; it stood for homosexuality, while Aphrodite Dionea (Dioning) represented heterosexuality.[4]

Ulrichs divided the term Uranian into two sub-classifications, the originally-written definitions of which are below:

a) Mannlinge: Körperhabitus, d. i. der Gesammtausdruck der Bewegungen, Gebärden und Manieren, Gemüthsart, Art der Liebessehnsucht und des geschlechtlichen Begehrens: sämmtlich männlich; weiblich also nur das nackte Geschlect der Seele, weiblich nur der Liebessehnsucht Richtung; d. i. gerichtet auf das männliche Geschlecht. |

a) Mannling: [Manling] (in) body habit, i.e. the overall expression of movements, gestures, manners, mood, and the type of love-longing and sexual desire are all male; femininity is therefore only within the sex of the psyche, meaning (one is) feminine only in pursuit of longing for love; i.e. being directed towards the male sex. |

| —Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, Forschungen über das Räthsel der mannmännlichen Liebe[2] |

History

Rights

Although significant work and literature regarding Uranians was done in Germany, laws criminalizing homosexuality (specifically under Paragraph 175 of the German legal code) caused the punishment of significant numbers of people identifying as Uranian throughout the entire time period during which the term was used. German legal author Ludwig Frey protested against these regulations, writing in his 1898 book Die Männer des Rätsels und der Paragraph 175 des Deutschen Reichsstrafgesetzbuches ("The Men of Riddles and Paragraph 175 of the German Imperial Criminal Code") that the state should stop punishing Uranians on account of their gender and sexuality:[5]

Das Los des Urnings wird dann immer noch kein beneidenswertes sein. Derselbe wird sich nie seines Daseins wie der Normalgeschlechtliche freuen können... |

The (life of the) lot of the Urnings will still not be an enviable one, as they will never be able enjoy existence as one of the normal sex does... |

| —Ludwig Frey, Die Männer des Rätsels und der Paragraph 175 des Deutschen Reichsstrafgesetzbuches[5] |

Individuals

Anna Rueling

Lesbian activist Anna Rueling used the term in a 1904 speech, "What Interest Does the Women's Movement Have in Solving the Homosexual Problem?"[6]

Dudley Ward Fay and Adolf

In 1922, Dudley Ward Fay, a psychoanalyst, visited a hospital for mental illnesses where he came into contact with a person, diagnosed with schizophrenia, who identified himself as a Uranian. (Fay uses he/him pronouns in his work to refer to the individual.) As part of an agreement reached concerning publication, Fay refers to the individual as Adolf, withholding his true identity.[7] There was no correlation between Adolf's schizophrenia diagnosis and his gender identity, with both relating to Adolf simply being a coincidence. Both before experiencing any symptoms of schizophrenia, and being released from the hospital, Adolf is reported to have made remarks and conducted himself in ways not traditionally seen as completely masculine.

In an interview with his parents, Adolf was described as having "never cared much for rough and tumble play and was inclined to play indoors and read rather than mingle with studier boys outside."[8] During his late-teens, Adolf became romantically involved with several men, occasionally making remarks that less-masculine men were superior to more masculine ones. During this same period, many of his actions and decisions became more rash, eventually culminating in an episode of psychosis requiring hospitalization. During the first day of his hospitalization, Adolf revealed to his doctor that he was "of the intermediate sex (not strongly masculine)".[9] Resulting from his schizophrenia, many of Adolf's statements became progressively more unclear and nonsensical, although reflecting on his gender identity was reoccurring theme:

| « | "I'm ambidextrous, ambisextrous. I'm intermediate sex."[10] | » |

| « | [I'm] Uranian. Uranus for the benefit of the Uranians.[11] | » |

Adolf claimed to have been born with female anatomical characteristics which he claimed to have been removed by his doctors. (This is likely a delusion resulting from his schizophrenia.) There is no evidence Adolf was born with these characteristics, although by the fourth month of Adolf's observation by Fay, he seems to have identified more so as Uranian and/or female than any point previously.

Many of Adolf's statements during his hospitalization were significantly affected by his schizophrenia, although upon his release, he still considered himself to be at least somewhat less male than his peers. Begun shortly before, and continued after his release, Fay attempted to pressure Adolf toward "trying to become male", which could possibly be considered a form of conversion therapy.[12]

References

- ↑ Original untranslated quote: "Ich bin vollkommen Weibling. Am liebsten beschäfftige ich mich mit weiblichen Handarbeiten. Ginge es nur an, so würde ich mich weiblich auch kleiden... Der Welt gegenüber muss ich mich ja in den Gebräuchen der Männer zeigen." from Ulrichs, Karl Heinrich (1870). Prometheus (in German). 10. Leipzig: Serbe'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. p. 14.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ulrichs, Karl Heinrich (1868). Forschungen über das Räthsel der mannmännlichen Liebe. Leipzig: C. Hübscher'sche Buchhandlung (Hugo Heyn). p. 10.

- ↑ Ulrichs, Karl Heinrich (1868). Forschungen über das Räthsel der mannmännlichen Liebe. Leipzig: C. Hübscher'sche Buchhandlung (Hugo Heyn). p. 6.

- ↑ Michael Matthew Kaylor, Secreted Desires: The Major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde (Brno, CZ: Masaryk University Press, 2006)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Frey, Ludwig (1898). Die Männer des Rätsels und der Paragraph 175 des Deutschen Reichsstrafgesetzbuches. Leipzig: Verlag von Max Spohr. p. 216.

- ↑ Meem, Deborah T.; Gibson, Michelle; Gibson, Michelle A.; Alexander, Jonathan (28 May 2018). Finding Out: An Introduction to LGBT Studies. SAGE. ISBN 9781412938655 – via Google Books.

- ↑ The Psychoanalytic Review. 9. Washington, D.C.: National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis. 1922. p. 267.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- ↑ The Psychoanalytic Review. 9. Washington, D.C.: National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis. 1922. p. 269.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- ↑ The Psychoanalytic Review. 9. Washington, D.C.: National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis. 1922. p. 275.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- ↑ The Psychoanalytic Review. 9. Washington, D.C.: National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis. 1922. p. 281.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- ↑ The Psychoanalytic Review. 9. Washington, D.C.: National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis. 1922. p. 283.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- ↑ The Psychoanalytic Review. 9. Washington, D.C.: National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis. 1922. p. 323.CS1 maint: date and year (link)