Gender neutral language in French: Difference between revisions

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

For instance, « <u>Les élèves</u> apprennent leur leçon. »; « <u>L'enfant</u> regarde la télévision. »; « <u>Les juges</u> ont pris leur décision. ». As singular articles indicate gender ('la' and 'le'), this technique works best with plural forms. However, it also works with singular forms if the noun begins with a vowel, because the article automatically becomes "l'...," which does not express gender. A drawback is that there are not epicene occupational titles for all professions or functions.<ref name=":0" /> | For instance, « <u>Les élèves</u> apprennent leur leçon. »; « <u>L'enfant</u> regarde la télévision. »; « <u>Les juges</u> ont pris leur décision. ». As singular articles indicate gender ('la' and 'le'), this technique works best with plural forms. However, it also works with singular forms if the noun begins with a vowel, because the article automatically becomes "l'...," which does not express gender. A drawback is that there are not epicene occupational titles for all professions or functions.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

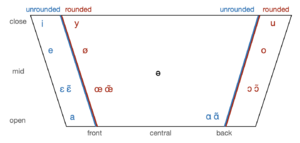

In certain Swiss-French varieties, as in the canton of Vaud, masculine and feminine words ending in '-é' resp. '-ée' are pronounced differently (i. e. 'une employée' [ynɑ̃plwaj<u>e:</u>]/[ynɑ̃plwaj<u>ej</u>] ''versus'' 'un employé' [ɛ̃nɑ̃plwaj<u>e</u>]/[œ̃nɑ̃plwaj<u>e</u>]). However, this linguistically conservative pronunciation is becoming increasingly marginal: it is primarily confined to Switzerland, and in major cities and among younger generations, the pronunciation is gradually converging with the standard French norm, meaning that the distinction between /e/ and /e:/ is being neutralized | In certain Swiss-French varieties, as in the canton of Vaud, masculine and feminine words ending in '-é' resp. '-ée' are pronounced differently (i. e. 'une employée' [ynɑ̃plwaj<u>e:</u>]/[ynɑ̃plwaj<u>ej</u>] ''versus'' 'un employé' [ɛ̃nɑ̃plwaj<u>e</u>]/[œ̃nɑ̃plwaj<u>e</u>]). However, this linguistically conservative pronunciation is becoming increasingly marginal: it is primarily confined to Switzerland, and in major cities and among younger generations, the pronunciation is gradually converging with the standard French norm, meaning that the distinction between /e/ and /e:/ (or /ej/, remnant from Franco-Provençal dialects, i. e. Patois, spoken in the region before linguistic homogenization) is being neutralized, resulting in a single phoneme /e/ and causing 'employé' and 'employée' to be pronounced identically. As a result, here, these words are considered orally epicene. | ||

=== Grammatically fixed gender nouns and impersonal formulations === | === Grammatically fixed gender nouns and impersonal formulations === | ||

Revision as of 20:40, 22 December 2023

| File:VisualEditor - Icon - Advanced - white.svg | Cmaass is working on this article right now, so parts of the article might be inconsistent or not up to our standards of quality. You are welcome to help, but please ask in the talk page before performing significant changes to this page. Note to editors: If this notice stays here for more than two weeks, feel free to replace it with {{incomplete}} or a similar maintenance template. |

Nowadays, French knows only two genders: feminine and masculine. Activists have started seeking solutions to degender the language as much as possible and, therefore, make it more inclusive. These solutions entail neologisms as well as non neologisms. Here we present the still ongoing quest for (grammatical) gender inclusivity in the French language.

Non neologisms

Refeminization

Prior to the 17th century, French, like Italian, Spanish, and other Romance languages, utilized feminine inflections to distinguish female professionals. However, for a range of reasons — both societal, such as misogyny,[1][2] and linguistic[3], as French was being standardized and dialect speakers were expected to learn French — grammarians ensured that these feminine designations were effectively removed from the language.[1]

Today, many people refer to the contemporary introduction of feminine designations as 'feminization,' believing that these occupational titles are newly coined terms. However, this is not the case, as they are being revived from an earlier iteration of the French language, making 'refeminization'[4] a more accurate term.

Even though it seems paradoxical, refeminization is part of a movement to degender the French language, as studies in various languages have demonstrated that the generic masculine, despite being considered gender-neutral by French prescriptive grammar,[5] is not actually cognitively neutral.[6][7] By incorporating the feminine form of a word, speakers acknowledge the presence of individuals of more genders than just one.

| Masculine | Feminine by the Académie | Refeminized |

|---|---|---|

| un auteur | une auteur(e) | une autrice |

| un professeur | une professeur(e) | une professeuse |

| un peintre | une peintre | une peintresse |

| un chirurgien | une femme chirurgien | une chirurgienne |

Doublets

For example, « Nous prions les étudiantes et (les) étudiants de remettre leur copie à la personne responsable ». Some people don't enjoy the repetition,[8] others consider that the doublets don't encompass all genders,[9] others again are unsure which form to mention first, since the order conveys information about the value the speaker gives to each item.[10]

Shortened doublets

The feminine suffix is attached to the masculine, rather than the whole word being repeated (as in classical doublets).[8][9]

| Middle dot | Dot | Parentheses | Slash | Dash |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| professionnel·les

professionnel·le·s |

acteur.rice | employé(e) | chanteur/euse | boulanger-ère |

Epicene person descriptions

For instance, « Les élèves apprennent leur leçon. »; « L'enfant regarde la télévision. »; « Les juges ont pris leur décision. ». As singular articles indicate gender ('la' and 'le'), this technique works best with plural forms. However, it also works with singular forms if the noun begins with a vowel, because the article automatically becomes "l'...," which does not express gender. A drawback is that there are not epicene occupational titles for all professions or functions.[4]

In certain Swiss-French varieties, as in the canton of Vaud, masculine and feminine words ending in '-é' resp. '-ée' are pronounced differently (i. e. 'une employée' [ynɑ̃plwaje:]/[ynɑ̃plwajej] versus 'un employé' [ɛ̃nɑ̃plwaje]/[œ̃nɑ̃plwaje]). However, this linguistically conservative pronunciation is becoming increasingly marginal: it is primarily confined to Switzerland, and in major cities and among younger generations, the pronunciation is gradually converging with the standard French norm, meaning that the distinction between /e/ and /e:/ (or /ej/, remnant from Franco-Provençal dialects, i. e. Patois, spoken in the region before linguistic homogenization) is being neutralized, resulting in a single phoneme /e/ and causing 'employé' and 'employée' to be pronounced identically. As a result, here, these words are considered orally epicene.

Grammatically fixed gender nouns and impersonal formulations

The table below shows gendered language on the left and neutral — i.e. grammatical gender that has nothing to do with biological sex or gender identity — language on the right.

| Inclusive gendered language | Inclusive neutral language |

|---|---|

| Les auditrices et auditeurs sont attentifs. | L'auditoire est attentif. |

| Les spectateurs et spectatrices sont très calmes aujourd'hui. | Le public est très calme aujourd'hui. |

| Explicit binary gender | Grammatically fixed gender |

|---|---|

| Je ne connais pas cet homme. | Je ne connais pas cette personne. |

| La mère de Jo ne parle pas le néerlandais. | Le parent de Jo ne parle pas le néerlandais. |

Proximity agreement

Up until the 18th century, the masculine gender did not always take precedence over the feminine in instances where the genders could theoretically be congruent: proximity[12] and free-choice agreement coexisted alongside the masculine-over-feminine rule.[2][3] For a significant portion of Old French history, proximity agreement was the most prevalent method for agreeing adjectives, past participles, etc. (cf. Anglade 1931:172).[13] Today, this agreement could facilitate gender equality in grammar instead of the masculine-over-feminine hierarchy that was suggested in the 17th and 18th century by French grammarians such as Malherbe, Vaugelas, Bouhours and Beauzée:

« Le genre masculin, étant le plus noble, doit prédominer toutes les fois que le masculin et le féminin se trouvent ensemble. » (Claude Favre de Vaugelas, Remarques sur la langue française, 1647).[1]

« Lorsque les deux genres se rencontrent, il faut que le plus noble l’emporte. » (Bouhours 1675).[5]

« Le genre masculin est réputé plus noble que le féminin à cause de la supériorité du mâle sur la femelle. » (Beauzée 1767).[5]

| Masculine-prevails-over-feminine rule | Proximity agreement |

|---|---|

| Ces œillets et ces roses sont beaux. | Ces œillets et ces roses sont belles. |

| Les nombreux filles et garçons. | Les nombreuses filles et garçons. |

Neologisms

Personal pronouns

Subject pronouns

French only distinguishes gender in the third-person singular (cf. 'elle' and 'il'). Up until the 12th century, French knew the neutral subject pronoun 'el'/'al'.[14] Today, 'el' cannot be reintroduced from Old French as it would sound identical to 'elle', the current feminin subject pronoun. As for 'al', it sounds like 'elle' in spoken Canadian French.[15] It could, however, still be a viable option for the rest of the Francophone community.[16] Nowadays, according to the Guide de rédaction inclusive (2021:14) from the Laval University,[11] the Guide de grammaire neutre et inclusive (2021:5) from Divergenres,[4] the Petit dico de français neutre/inclusif (2018) from La vie en Queer,[17] and Wiki Trans (2019),[18] the most widely adopted subject (neo)pronoun is 'iel'. It was added to the prestigious dictionary Le Robert in 2021.[19] Alongside 'iel', Canadian French also uses 'ille'.[4][15] In metropolitan France, the pronoun 'al', proposed by linguist Alpheratz in their book Grammaire du français inclusif (2018) has gained some recognition. The table below presents the primary gender-neutral subject pronouns found in the French-speaking world.

| gender-neutral subject pronouns | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant usage | iel [jɛl] | ille [ij][15] | al |

| Peripheral usage | ol | ul | ael |

Clitic and tonic pronouns

French distinguishes between clitic and tonic pronouns. A clitic is a word that attaches in a syntactically rigid way to another word to form a prosodic unit with it, lacking prosodic as well as distributional autonomy.[20] Currently, there is no prevailing gender-neutral clitic direct object personal pronoun; the most common ones are detailed below.

| Subject | Direct object | Indirect object |

|---|---|---|

| il | le, (l') | lui |

| elle | la, (l') | lui |

| iel | lae [lae]/lo/li/lu/lia, (l') | lui |

| ils | les | leur |

| elles | les | leur |

| iels | les | leur |

Tonic pronouns are also called 'autonomous' because, in opposition to clitics, they form their own prosodic unit and can stand alone in the sentence, hence their distribution is not as fixed as the clitics' one.[20] There are currently two competing systems:[18][17] one consists in syncretizing (cf. analogical levelling)[21] clitic and tonic pronouns, following the paradigm of standard French 'elle', which equates keeping the gender-neutral subject pronoun — be it 'iel', 'ille', 'al' or 'ol', etc. — as such; the other approach, exemplified in the table below with 'iel', supports differentiating (cf. analogical extension)[21] clitics from tonic pronouns, thereby aligning with the paradigm of 'il'.

| Clitic subject pronoun | Tonic pronoun |

|---|---|

| il | lui |

| elle | elle |

| iel | ellui [ɛllɥi] |

| ils | eux |

| elles | elles |

| iels | elleux [ɛllø] |

Determiners

Indefinite and definite article

The distinction between 'analytic gender-neutral' versus 'synthetic gender-neutral' is usually referred to as 'inclusif' versus 'neutre'.[4] Compounds — such as 'maon', from 'ma' and 'mon' — and portmanteau words, like 'utilisateurice', could be cognitively interpreted as neutral; at least, there have been no psycholinguistic studies disconfirming this, to the extent that these forms could technically also be called neutral. Furthermore, since gender-neutral forms are inherently inclusive of all genders, there is no reason why they cannot be called that way either. The subsequent interchangeability of these terms makes them unsuitable for differentiating these two methods of creating gender-neutral/gender inclusive words in French. For this reason, the following table distinguishes them based on their morphological properties — blend words being more analytical and non blend words being more synthetic.

The currently most widely accepted neutral forms are denoted in italics in the table. Apart from them, most of the forms depicted in the tables are not in use. The tables thus merely represent suggestions that have been made for degendering French, and feature the items that have been retained by most blogs, researchers and LGBT communities in the French-speaking world.

The underlining of phonemes in the IPA transcription of certain words does not carry any phonetic meaning: it is used solely to highlight which phonetic elements from the feminine and masculine forms have been incorporated into the analytic gender-neutral neologism.

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indefinite article | un [œ̃]/[ɛ̃] | une [yn] | eune [œn] | an [ɑ̃]/[an] |

| Definite article | le | la | lae [lae], lea [ləa] | lo, li, lu, lia |

'an' is quite common, particularly in the [ɑ̃] pronunciation, where it shares a core feature with 'un': both consist solely of a nasal vowel. 'eune' [œn] combines the roundedness and degree of aperture of 'un' [œ̃] with the terminal nasal consonant [n] of 'une'. In metropolitan French, where 'un' is typically pronounced as [ɛ̃], 'eune' shares a phonetic characteristic with 'une' through the final [n], and one with 'un' through the similar degree of aperture of their vocalic nucleus.

A drawback of 'an' pronounced as [ɑ̃] is its nasality, a factor known for making vowels challenging to distinguish and learn, even for native French speakers.[22] Consequently, [ɑ̃] might be perceived as a mispronunciation of 'un' or simply not distinct enough from 'un' to be recognized as a different morpheme.

Possessive adjectives

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1SG | mon | ma | maon [maõ] | man [mɑ̃]/[man], mi(ne) |

| 2SG | ton | ta | taon [taõ] | tan [tɑ̃]/[tan], ti(ne) |

| 3SG | son | sa | saon [saõ] | san [sɑ̃]/[san], sine [sin] |

The possessive adjectives 'mon', 'ton', and 'son', which are generally masculine, are also used as feminine possessive adjectives when combined with a feminine noun that begins (phonetically) with a vowel: 'mon amie', 'ton employée', 'son hôtesse', etc. Therefore, there is no need to use a possessive neologism in words starting with vowels, as the masculine and feminine gender are syncretized in this context.

The pronunciation [sɑ̃] of 'san' is a homophone of 'sang' ('blood'). Alpheratz proposes 'mu(n)', 'tu(n)', 'su(n)'[16] as synthetic forms. However, 'tu(n)' is a homophone of the subject pronoun 'tu', and <u> — i. e. [y] — is a linguistically marked phone.[23][24] Alternative forms could be 'mi(ne)', 'ti(ne)', 'sine', as only the roundness parameter (cf. [y] and [i] in the IPA) distinguishes them from the original neologisms from Alpheratz. 'sine' would be the only one without an optional '-ne' ending to avoid homophony with 'si' (i. e. 'if'). Similar-sounding possessive adjectives can be found in Spanish ('mi'), in English ('my'), in Swedish ('min', 'din', 'sin', the last one being a gender-neutral reflexive possessive pronoun),[25] in Norwegian,[26] in Swiss-German,[27] and in other Germanic languages. As 60% of of humans are multilingual,[28] cross-linguistic influence could be used to facilitate the memorization and adoption of neologisms.[29][30]

Demonstrative adjective

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ce/cet | cette | cèd | ces |

La vie en Queer proposes 'cet', which sounds the same as the feminine 'cette'; Divergenres retains 'cèx', but notes that it sounds like the word 'sexe'. A third possibility is to voice or to devoice the final consonant of the feminine word, for instance turning [t] to [d], or [g] to [k]. This would allow the word to remain easily recognizable while being distinct from both the masculine and the feminine forms. This approach has the advantage of minimizing misunderstandings and memorization effort.

Non personal pronouns

Possessive pronouns

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | le mien [lə mjɛ̃] | la mienne [la mjɛn] | lae mienn [lae mjɛ̃n] | lo miem |

| Plural | les miens [le mjɛ̃] | les miennes [le mjɛn] | les mienns [le mjɛ̃n] | les miems |

Currently, there is no established combination of definite article and possessive pronoun. In this table, the definite article "lae" is simply paired with the possessive pronoun "mienn" for morphological reasons, as both words are of the analytic gender-neutral type. This also applies to the definite article "lo" and the possessive pronoun "miem", both of which are of the synthetic type.

Demonstrative pronouns

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | celui [səlɥi] | celle [sɛl] | cellui [sɛlɥi] | |

| Plural | ceux [sø] | celles [sɛl] | celleux [sɛlø] | ceuxes [søks] |

Indefinite pronouns

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aucun·e | aucun [okœ̃]/[okɛ̃] | aucune [okyn] | aucunn [okœ̃n]/[okɛ̃n], aucueune [okœn] | aucan [okɑ̃]/[okan] |

| chacun·e | chacun [ʃakœ̃/[ʃakɛ̃] | chacune [ʃakyn] | chacunn [ʃakœ̃n]/[ʃakɛ̃n], chacueune [ʃakœn] | chacan [ʃakɑ̃]/[ʃakan] |

| certain·e | certain [sɛʁtɛ̃] | certaine [sɛʁtɛn] | certainn [sɛʁtɛ̃n] | certan [sɛʁtɑ̃]/[sɛʁtan] |

| tout·e | tout | toute | toude | |

| tous/toutes | tous | toutes | toustes | |

| quelqu'un·e | quelqu'un [kɛlkœ̃]/[kɛlkɛ̃] | quelqu'une [kɛlkyn] | quelqu'unn [kɛlkœ̃n]/[kɛlkɛ̃], quelqu'eune [kɛlkœn] |

The indefinite pronoun 'quelqu'une' is extremely rare in modern French and its pendant 'quelqu'un' not necessarily perceived as masculine, thus it is not clear how essential the degendering of this pronoun is.

Nouns and adjectives

Words such as 'professionnel' and 'professionnelle', which are orally epicene and, thus, indistinguishable in speech, are not included; the use of their shortened doublet form enables inclusivity and gender-neutrality in written language.

Endings from Latin '-or' and '-rix'

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -eur/-euse | enquêteur | enquêteuse | enquêteureuse | enquêtaire |

| -eur/-rice | acteur | actrice | acteurice | actaire |

| -eur/-_resse1 | docteur | doctoresse[31] | docteuresse | doctaire |

| -eur/-_resse2 | enchanteur | enchanteresse | enchanteuresse | enchantaire |

| -e/-esse | maître | maîtresse | maîtré/maîtrè (or maîtræ) | maîtrexe |

| -ard/-asse | connard | connasse | connarde |

The analytic gender-neutral forms derived from words that originate from Latin '-or' and '-rix' are already being used,[32] although they have not been officially recognized by any French dictionary yet. Some podcasts where you can hear them are Les Couilles sur la table, Parler comme jamais and Papatriarcat.

Synthetic gender-neutral forms have the advantage of preserving the original syllable number of the word, making them less cumbersome than analytic forms. Moreover, the '-aire' suffix does already exist in contemporary French, forming epicene nouns like 'un·e destinataire', 'un·e secrétaire', 'un·e volontaire', 'un·e bibliothécaire', etc. However, several psycholinguistic studies conducted in French[33][34] and in German[35] have found that "gender-unmarked forms are not fully effective in neutralizing the masculine bias"[36] and that "contracted double forms [such as acteur·ice] are more effective in promoting gender balance compared to gender-unmarked forms."[36] Regarding this issue, specifically, analytic gender-neutral forms could then be a more effective solution than synthetic ones.

Endings with '-x' in the masculine

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -eux/-euse | amoureux | amoureuse | amoureuxe [amuʁøks] | |

| -eux/-esse | dieu | déesse | dieuesse | dieuxe |

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -x/-sse | roux | rousse | rouxe | |

| -x/-ce | doux | douce | douxe |

The synthetic gender-neutral forms in which the silent consonant of the masculine form becomes audible mantain the original number of syllables. They have an audible suffix, like the feminine forms do, without that suffix being the same as the feminine. This places them between the feminine and the masculine forms. Additionally, the fact that the audible consonant in gender-neutral form matches the consonant in the masculine suffix could facilitate the learning of these neologisms for literate French speakers. However, in cases where the masculine does not contain a silent <x> and the feminine has a distinctive suffix, such as with 'dieu, déesse', adopting the analytic approach may be more consistent in terms of spelling and inclusivity (see previous paragraph).

Endings with nasal vowels in the masculine form

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -ain/-aine | écrivain [ekʁivɛ̃] | écrivaine [ekʁivɛn] | écrivainn [ekʁivɛ̃n] | écrivan |

| -ain/-ine | copain [kɔpɛ̃] | copine [kɔpin] | copainn [kɔpɛ̃n], copaine [kɔpɛn] | |

| -in/-ine | cousin [kuzɛ̃] | cousine [kuzin] | cousinn [kuzɛ̃n] | cousaine [kuzɛn] |

| -an/-anne | paysan [pɛizɑ̃] | paysanne [pɛizan] | paysann [pɛizɑ̃n] | paysaine [pɛizɛn] |

| -ien/-ienne | citoyen [sitwajɛ̃] | citoyenne [sitwajɛn] | citoyenn [sitwajɛ̃n] | citoyan |

| -un/-une1 | brun [bʁœ̃]/[bʁɛ̃] | brune [bʁyn] | brunn [bʁœ̃n]/[bʁɛ̃n] | braine, bran |

| -un/-une2 | opportun [ɔpɔʁtœ̃]/[ɔpɔʁtɛ̃] | opportune [ɔpɔʁtyn] | opportunn [ɔpɔʁtœ̃n]/[ɔpɔʁtɛ̃n] | opportaine |

| -on/-onne | mignon [miɲõ] | mignonne [miɲɔn] | mignonn [miɲõn] | mignaine, mignan |

The '-aine' suffix has gained popularity. However, its use in monosyllabic words like 'brun·e' may hinder comprehension, which could explain why 'bran', a form that preserves the nasality of the final vowel while only changing its place of articulation, is more widespread. Words with a '-ien/-ienne' (and obviously also '-ain/-aine') suffix cannot form a synthetic gender-neutral form with '-aine', as this would result in a word pronounced exactly the same way as the feminine one (cf. 'citoyenne'). Here, the synthetical neutral forms created with '-an' only retain masculine phonetic traits (i. e. its manner of articulation — vocalic — and its nasality trait — which is positive). Theoretically, this could lead to similar issues as discussed in the Endings from Latin '-or' and '-rix' subchapter. The same could be true with synthetic gender-neutral forms ending in '-aine', but this time in favour of the feminine. However, even though the suffix '-aine' could sound feminine, the resulting form is still easily distinguishable from the original one, since the vowels implied are oral and not nasal, and can therefore be less easily mistaken for mispronunciations — while 'écrivan', 'citoyan' and 'bran' could be (for more information, see the Indefinite and definite article subchapter).

Endings with silent consonant X in the masculine and audible consonant X in the feminine

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -t/-te | pâlot | pâlotte | pâlode, pâlat, pâlasse | |

| -d/-de | grand | grande | grante, granxe, gransse | |

| -iet/iète | inquiet | inquiète | inquiède | |

| -g/gue | oblong | oblongue | oblonk | |

| -er/-ière | premier [pʁəmje] | première [pʁəmjɛʁ] | premiérère, premiér [pʁəmjeʁ] | |

| -c/-che | blanc | blanche | blank | |

| -s/-se | antillais | antillaise | antillaisse | |

| -s/-che | frais | fraîche | fraîchais | fraisse |

| -s/-sse | bas | basse | babasse | base |

As the table demonstrates, no approach has achieved widespread acceptance among this category of nouns and adjectives. As discussed in the Demonstrative adjective subchapter, one intuitive approach to creating a gender-neutral form involves making the silent consonant of the masculine form audible in the neologism while voicing or devoicing it, so that its pronunciation is different from the feminine form — e. g.: 'palôt' → 'palôte' (sounds like 'pâlotte') → 'pâlode' . However, masculine words ending in a silent <s> pose a challenge: when put in the feminine form, the <s> can either become a voiced sibilant [z] or a voiceless sibilant [s] (the outcome [ʃ] is irrelevant in this issue). This inconsistency means that the silent <s> of the masculine form can represent either a voiced or a voiceless sound. While the silent consonants of other words can simply be transformed into their voiceless resp. voiced counterparts to differentiate them from the feminine, creating gender-neutral forms from words like "antillais·e" and "bas·e" requires more careful consideration. If the feminine form is pronounced with a [s], the pronunciation of the gender-neutral form must be [z] to avoid homophony; conversely, if the feminine form is pronounced [z], the gender-neutral form's pronunciation must be [s] to maintain distinctiveness.

Endings with a rounded vowel in the masculine and '-_(l)le' in the feminine

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -eau/-elle | jumeau | jumelle | jumelleau, jumeaulle | |

| -ou/-olle | fou | folle | follou, foulle | |

| -aux/-ales | spéciaux | spéciales | spécialaux, spéciaules | |

| -eux/-lle | vieux/vieil | vieille | vieilleux, vieuille |

The pronunciation of /a/ as [ɔ] in Canadian French can lead to ambiguity in gender-neutral forms like 'spéciaules', as they could be interpreted as the feminine singular and plural, or masculine singular form of 'spécial·e'.

Endings with consonant X in the masculine and consonant X with phonetic change triggered by presence of final '-e' in the feminine

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -c/-che | sec | sèche | seckèche, sèchec | |

| -f/-ve | naïf | naïve | naïfive, naïvif |

Florence Ashley argues that the order in which the feminine and masculine morphemes are combined does not matter.[15] Usage, intelligibleness and personal preference ultimately determine which forms will gain traction. However, the prosodic sequencing of syllables in French can impact intelligibility. For instance, in the pronunciation of 'naïvif' (neutral form) as [na'i'vif], contrary to 'naïfive', the end of the word is acoustically identical to 'vif' (i. e. 'vivacious') and can thus lead to confusion.

Some gender-neutral nouns from irregular substantives

| Masculine | Feminine | Analytic gender-neutral | Synthetic gender-neutral |

|---|---|---|---|

| roi | reine | roine | |

| héros | héroïne | héroïnos | héroan [eʁoɑ̃]/[eʁoan], héroal |

| frère | sœur | frœur, srère | adelphe |

| Monsieur | Madame | Monestre |

Illustrative narrative text with neologisms

The neologisms that a primarily depicted here are the ones that either are analytical — as they have been shown to be cognitively more inclusive than some synthetic ones —, easier to pronounce, cross-linguistically relevant or the most widespread.

"Lae maîtré accueillent les enfants et leur demande de prendre place. La leçon du jour concerne les métiers. L’instituteurice interroge les élèves sur leurs souhaits professionnels et les professions exercées par les membres de leur famille. An élève dans la deuxième rangée prend la parole :

- Plus tard, j’aimerais travailler en tant qu’infirmiér ou chirurgienn, parce que mi frœur aîné·e, Amel, est an brillande médecin à l’hôpital de Lyon et que je l’admire beaucoup. Malheureusement, iel est très occupé·e en ce moment et je ne peux lae voir et passer du temps avec ellui que le week-end.

An autre élève réagit :

- Quand j’étais à l’hôpital parce qu’il y avait un problème avec mon glucomètre, lae docteuresse qui s’est occupé·e de moi m’a dit qu’iel s’appelait Amel ! Est-ce que ton adelphe est rouxe, par hasard ?

- Non, iel est pas rouxe, mais iel se teint régulièrement les cheveux avec du henné !

- Alors je suis sur·e que c'était ti frœur ! Moi, quand je serai grante, j’aimerais m’occuper aussi bien des autres que le fait Amel. J’aimerais devenir éducateurice spécialisé·e.

- Moi aussi j’adore aider les autres ! Souvent, le matin, j’aide mi jumeaulle à s’habiller, à préparer sa récré et à mettre ses chaussures, parce qu’iel a un chromosome de plus que moi alors certaines choses sont moins faciles pour ellui. Il faut être patiende et très douxe parce qu’iel fait pas ça exprès ! J’écrirai des livres sur ce dont les personnes qui réfléchissent différemment ont besoin et je découvrirai pourquoi elles pensent comme ça : du coup, quand je serai vieuille, je serai écrivainn-chercheureuse.

- Comment ça, quand tu seras vieilleux ? Tu crois que tu vas commencer à travailler quand ?

- Je sais pas, quand je serai adulte, quand je serai vieuille quoi.

- Ce que tu es mignonn de penser que je suis vieilleux, moi, merci.

- (ricanements)

- Moi, je suis un peu inquiède parce que je ne sais pas ce que je voudrais être plus tard.

- Peut-être tes camarades peuvent te donner des idées.

- Je peux te raconter ce que fait mi grante cousaine, Anh : comme iel adore les animaux, iel est devenu·e paysann, comme ça iel peut les caresser tous les jours !

- Mi voisinn, à moi, iel est enseignande de Yoruba, et parfois iel donne même des cours à domicile.

- Mais, je lae connais, ti voisan André·e, iel est kazakhstanaisse, ses langues maternelles, c'est le russe et le kazakh, iel peut pas enseigner le Yoruba.

- Bien sûr qu’iel peut ! Tu as pas besoin d’avoir une nationalité spécifique pour savoir une langue ! La preuve, moi je suis allemante et italienn, mais je parle que français.

- On a discuté de beaucoup de métiers dans le monde du social. Est-ce que vous connaissez des gens dans des domaines plus techniques ?

- Oui, mi paman, par exemple, iel travaille en tant qu’ingénieureuse de logiciel. Parfois, iel est de piquet et, ces soirs-là, quand quelque chose tombe en panne, iel devient toude blank et se précipite sur son ordinateur pour réparer le problème. Mapa dit toujours que je dois pas rire de Paman, dans ces moments, mais j’arrive pas à me retenir, la tête qu’iel fait est trop drôle.

- Et ti paman, iel fait quoi ?

- Ellui, iel est politicienn : iel vérifie que vous continuez à toustes vous comporter en bonns citoyenns !

- Tu es bien naïfive si tu penses qu’en général on se comporte en bonns citoyans !

- Moi, j'ai pas pu parler encore.

- Vas-y, Ariel·le, on t'écoute.

- Mi tancle, iel est championn de para hockey.

- C'est pas un métier, ça, le sport.

- Oh que si ! Iel s'entraîne dur tous les jours, d'ailleurs sine entraîneureuse est très fier·e d'ellui parce qu'iel est an capitainn si engagé·e que son équipe est régulièrement sélectionnée pour les Jeux Paralympiques. Moi, plus tard, j'aimerais aussi être an sportifive de haut niveau, comme ellui.

- Bien, sur ce, je vous propose à toustes d'aller enfiler vos affaires de sport : on se retrouve dans la salle de gymnastique pour une partie de unihockey.

Les élèves :

- Yes!"

Discussion

According to linguist Roswitha Fischer, citing Renate Bartsch,[38] the adoption of neologisms into a language's lexicon depends on three factors:

- Prestige: The neologism must be championed by a group of influential individuals who hold social, political, and economic power.

- Written Usage: The neologism must gain traction in written communication, becoming accepted in literature, media, and formal communication.

- Linguistic Contact: The neologism must circulate in areas where multiple dialects and varieties of the language converge, fostering mutual understanding and assimilation.[39]

Currently, gender-neutral French neologisms lack widespread adoption, even within LGBT and nonbinary communities. Their presence is marginal in written form,[40][41] and their usage in spoken language limited. However, the Internet serves as an area for these neologisms to reach a global audience of Francophone speakers from Africa, America, Europe, and minority language communities all around the world. Additionally, descriptive approaches to language (cf. Le Robert), contrary to prescriptive approaches (cf. L'Académie), have lead to the acceptance of one of them — 'iel' — in written discourse.

For neologisms to gain wider adoption, they must be learnable and user-friendly. This means they should be easy to understand and easy to remember (due to morphological motivation); easy to pronounce while adhering to the phoneme inventory and phonotactics of the language; familiar to the target audience; and responsive to a genuine need.[39] If these criteria are met, neologisms will start being adopted by avant-garde language users. As these avant-garde figures gather large online communities, the frequency of usage of these neologisms will increase, fostering familiarity among the Francophone community. From then, some of these neologisms could potentially enter the standard vocabulary.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Becquelin, Hélène: Langage en tout genre. Argument historique. Université de Neuchâtel. Online at: https://www.unine.ch/epicene/home/pourquoi/argument-historique.html (12.12.2023).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Viennot, Eliane (2023): Pour un langage non sexiste ! Les accords égalitaires en français. Online at: https://www.elianeviennot.fr/Langue-accords.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 MOREAU, Marie-Louise. L’accord de proximité dans l’écriture inclusive. Peut-on utiliser n’importe quel argument ? In : Les discours de référence sur la langue française [en ligne]. Bruxelles : Presses de l’Université Saint-Louis, 2019 (généré le 12 décembre 2023). Disponible sur Internet : <http://books.openedition.org/pusl/26517>. ISBN : 9782802802457. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pusl.26517.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Divergenres (2021): Guide de grammaire neutre et inclusive. Québec. Online at: https://divergenres.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/guide-grammaireinclusive-final.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Alchimy (2017): « Le masculin l’emporte sur le féminin » : Bien plus qu’une règle de grammaire. Usbek&Rica: "Selon Le Bon Usage de Maurice Grevisse, l'adjectif se met donc au 'genre indifférencié, c'est-à-dire au masculin'."

- ↑ Tibblin, J., Weijer, J. van de, Granfeldt, J., & Gygax, P. (2023). There are more women in joggeur·euses than in joggeurs : On the effects of gender-fair forms on perceived gender ratios in French role nouns. Journal of French Language Studies, 33, 28‑51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959269522000217.

- ↑ Heise, E. (2003). Auch einfühlsame Studenten sind Männer: Das generische Maskulinum und die mentale Repräsentation von Personen [Even empathic students are men: The generic masculine and the mental representation of persons]. Verhaltenstherapie & Psychosoziale Praxis, 35(2), 285–291.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 OMPI (2022): Guide de l’OMPI pour un langage inclusif en français. Genève. Online at: https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/women-and-ip/fr/docs/guidelines-inclusive-language.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ménard, Jean-Sébastien (2021): Pour un français neutre et une inclusion des personnes non binaires : une entrevue avec Florence Ashley. Longueuil. Online at:https://www.cegepmontpetit.ca/static/uploaded/Files/Cegep/Centre%20de%20reference/Le%20francais%20saffiche/Une-entrevue-avec-Florence-Ashley.pdf (12.12.2023), p. 13, p. 6.

- ↑ Pascal Gygax, Manon Boschard, Geoffrey Cornet, Magali Croci, Natasha Stegmann (2021): Les outils - la (re)féminisation. Langage inclusif. Online at: https://tube.switch.ch/videos/0xwYktNzRp, 00:50.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Université Laval (2021): Guide de rédaction inclusive. Online at: https://www.ulaval.ca/sites/default/files/EDI/Guide_redaction_inclusive_DC_UL.pdf.

- ↑ EPFL (2023): L’accord de proximité. Online at:https://www.epfl.ch/about/equality/fr/langage-inclusif/guide/principes/accord/ (12.12.2023).

- ↑ Anglade, Joseph (1931): Grammaire élémentaire de l'ancien français. Paris: Armand Colin, 157-196. Online at: https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Grammaire_%C3%A9l%C3%A9mentaire_de_l%E2%80%99ancien_fran%C3%A7ais/Chapitre_6.

- ↑ Marchello-Nizia Christiane. Le neutre et l'impersonnel. In: Linx, n°21, 1989. Genre et langage. Actes du colloque tenu à Paris X-Nanterre les 14-15-16 décembre 1988, sous la direction de Eliane Koskas et Danielle Leeman. 173-179. DOI : https://doi.org/10.3406/linx.1989.1139. Online at: www.persee.fr/doc/linx_0246-8743_1989_num_21_1_1139.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Florence Ashley (2019): Les personnes non-binaires en français : une perspective concernée et militante. In: H-France Salon 11(14), p. 6.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Alpheratz (2018): Genre neutre.TABLEAUX RÉCAPITULATIFS de mots de genre neutre (extraits). Online at: https://www.alpheratz.fr/linguistique/genre-neutre/.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 La vie en Queer (2018): Petit dico de français neutre/inclusif. Online at: https://lavieenqueer.wordpress.com/2018/07/26/petit-dico-de-francais-neutre-inclusif/.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Wiki Trans (2019): Comment parler d'une personne non binaire ? Online at: https://wikitrans.co/2019/12/25/comment-parler-dune-personne-non-binaire/.

- ↑ Radio Télévision Suisse (2021): L'entrée du pronom "iel" dans Le Robert provoque des remous. Online at: https://www.rts.ch/info/monde/12651159-lentree-du-pronom-iel-dans-le-robert-provoque-des-remous.html.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Michel Launey, Dominique Levet (2017): La catégorie de la personne. Maison des Sciences des l'Homme Paris Nord. Online at: https://web.ac-reims.fr/casnav/enfants_nouv_arrives/aide_a_la_scolarisation/LGIDF/LGIDF.LA%20PERSONNE.02.03.17.pdf.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Campbell, Lyle (1998): Historical Linguistics. An Introduction. First ed. Cambridge/Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- ↑ Etienne Sicard, Anne Menin-Sicard, Gabriel Rousteau. Oppositions de voyelles orales et nasales : identification des formants selon le genre. INSA Toulouse. 2022. ffhal-03826558v2f.

- ↑ Rice, K. (2007). Markedness in phonology. In: The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology, 79-98. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511486371.005.

- ↑ Carvalho, Joaquim (Brandão de) (2023): “From binary features To elements: Implications for markedness theory and phonological acquisition”. In: Radical: A Journal of Phonology 3, 346-384. Here specifically: 352-353.

- ↑ Duolingo Wiki: Swedish Skills. Possessives. Online at:https://duolingo.fandom.com/wiki/Swedish_Skill:Possessives.

- ↑ Norwegian University of Science and Technology (no data): 8 Grammar. Possessives. Online at: https://www.ntnu.edu/now/8/grammar.

- ↑ Klaudia Kolbe (2017): Schweizerdeutsch. Schlüssel zu den Übungen. Online at: https://silo.tips/download/schweizerdeutsch-schlssel-zu-den-bungen.

- ↑ Sean McGibney (2023): What Percentage of the World’s Population is Bilingual? Introduction to Bilingualism: Exploring the Global Language Diversity. Online at: https://www.newsdle.com/blog/world-population-bilingual-percentage.

- ↑ VAN DIJK C, VAN WONDEREN E, KOUTAMANIS E, KOOTSTRA GJ, DIJKSTRA T, UNSWORTH S. (2022): Cross-linguistic influence in simultaneous and early sequential bilingual children: a meta-analysis. In: Journal of Child Language 5, :897-929. doi:10.1017/S0305000921000337.

- ↑ van Dijk C, Dijkstra T, Unsworth S. Cross-linguistic influence during online sentence processing in bilingual children (2022): In: Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 4, 691-704. doi:10.1017/S1366728922000050.

- ↑ Doctoresse Joséphine Tornay. Online at: https://cm-latour.ch/team/josephine-tornay-medecine-interne-generale/. Very common Swiss French denomination for female doctors.

- ↑ Viennot, Eliane (2023): Pour un langage non sexiste ! Acteurice, visiteureuse... Des néologismes de plus en plus employés. Online at: https://www.elianeviennot.fr/Langue-mots.html.

- ↑ Brauer, M., and Landry, M. (2008): Un ministre peut-il tomber enceinte? L'impact du générique masculin sur les représentations mentales. In: L'Année Psychol. 108, 243-272. DOI: 10.4074/S0003503308002030.

- ↑ Xiao, H., Strickland, B., and Peperkamp, S. (2023): How fair is gender-fair language? Insights from gender ratio estimations in French. In: J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 42, 82-106. DOI: 10.1177/0261927X221084643.

- ↑ Stahlberg, D., Sczesny, S., and Braun, F. (2001): Name your favorite musician: effects of masculine generics and of their alternatives in German. In: J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 20, 464-469. DOI: 10.1177/0261927X01020004004.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Spinelli, Elsa/Chevrot, Jean-Pierre/Varnet, Léo (2023): Neutral is not fair enough: testing the efficiency of different language gender-fair strategies. In: Front. Psychol. 14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1256779.

- ↑ CNRTL (2012): -EUX, élément formant. Online at: https://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/-eux.

- ↑ Bartsch, Renate (1987): Sprachnormen: Theorie und Praxis: Studienausgabe. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110935875,

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Fischer, Roswitha (1998): Lexical Change in Present-Day English. A Corpus-Based Study of the Motivation, Institutionalization, and Productivity of Creative Neologism. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag. Online at: https://books.google.ch/books?id=H93nAVbwZwwC&printsec=frontcover&hl=de#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ Café aux étoiles. maison d'édition sereine et onirique (no data): Littérature. Online at: https://cafeauxetoiles.fr/litterature/.

- ↑ Les Ourses à plumes. Webzine féministe (2022): Les elfes noirs ne sont jamais noirs (1) : enjeux de la représentation dans les fictions de l'imaginaire. Online at: https://lesoursesaplumes.info/tag/une/.