English neutral pronouns

Data provided by the 2019 Gender Census.[1] |

English neutral pronouns are useful not only when writing documents that need to use inclusive language, but also for any nonbinary people who prefer not to have their pronouns imply that they are female or male. As shown in surveys, many nonbinary people are okay with being called "he" or "she," but there are also many nonbinary people who don't want to be called either of these. The surveys show that the most popular gender-neutral pronoun for nonbinary people is singular they, but nearly as many prefer or accept some other neutral pronoun. See examples of this in pronouns in use for nonbinary people.

History[edit | edit source]

In English, people are usually called by a pronoun that implies their gender. For example, she for women, and he for men. The use of singular they as a gender-neutral pronoun has been documented as standard usage in English throughout the past thousand years. However, prescriptive grammarians in the late eighteenth century decided that it was bad grammar because it works like a plural and because it isn't done in Latin.[2]

Prescriptive grammarians of the late eighteenth century instead recommended using "he" as a gender-neutral pronoun when one is needed, instead of "singular they."[3] However, "gender-neutral he" results in writings that are unclear about whether they mean only men or not, which makes problems in law.[4]

Regional nominative pronouns[edit | edit source]

There have been some native English dialects that have their own gender-neutral pronouns, such as a, ou, and yo. These are often regional. One curious thing that a, ou, and yo all have in common is that they have only been recorded in their nominative form. It's possible that these three sets of pronouns may not actually have other forms (possessive, reflexive, etc). For this reason, these three sets of native English pronouns are listed separately from the other pronouns on this page that have complete forms. Although it's easy to make up more forms for these pronouns (such as inventing "ouself" [sic]), this is not what linguists have recorded in use.

A[edit | edit source]

A (nominative form only). "In 1789, William H. Marshall records […] Middle English epicene ‘a’, used by the 14th century English writer John of Trevisa and both the OED and Wright's English Dialect Dictionary confirm the use of ‘a’ for he, she, it, they, and even I. This ‘a’ is a reduced form of the Anglo-Saxon he = ‘he’ and heo = ‘she’.”[5] [6] Some living British dialects still use the gender-neutral "a" pronoun.[7]

Ou[edit | edit source]

Ou (nominative form only) was first recorded in a native English dialect in the sixteenth century. "In 1789, William H. Marshall records the existence of a dialectal English epicene pronoun, singular ou: '"Ou will" expresses either he will, she will, or it will.' Marshall traces ou to Middle English epicene a, used by the fourteenth-century English writer John of Trevisa, and both the OED and Wright's English Dialect Dictionary confirm the use of a for he, she, it, they, and even I." In K. A. Cook's short story "The Differently Animated and Queer Society," the queer character Moon asks to be called by "ou" pronouns.[8]

Yo[edit | edit source]

Yo (nominative form only). In addition to an interjection and greeting, "yo" is a gender-neutral pronoun in a dialect of African-American Vernacular English spoken by middle school students in Baltimore, Maryland, the student body of which is 97% African-American. These students had spontaneously created the pronoun as early as 2004 and commonly used it. A study by Stotko and Troyer in 2007 examined this pronoun. The speakers used "yo" only for same-age peers, not adults or authorities. They thought of it as a slang word that was informal, but they also thought of it as just as acceptable as "he" or "she". "Yo" was used for people whose gender was unknown, as well as for specific people whose gender was known, often while using a pointing gesture at the person in question. The researchers collected examples of the word in use, such as "yo threw a thumbtack at me," "you acting like I said what yo said," and "she ain't really go with yo." The researchers only collected examples of "yo" used in the nominative form. That is, they found no possessive forms such as "yo's," and no reflexive forms such as "yoself." As such, "yo" pronouns might be used only in nominative form, similar to another native English gender-neutral pronoun, "a." Either that, or these forms exist, and the researchers just didn't collect them.[9][10]

Neopronouns[edit | edit source]

Neopronoun is a category for any English pronouns that are independent from traditional third person English pronouns. In the strictest sense, a neopronoun is a singular third-person pronoun which is not he/him, she/her, it/its, or they/them.[11] There is some disagreement in the nonbinary community on whether "it/its" should be considered a neopronoun when used for a person[12], as the traditional usage is for animals, objects, and concepts.

Seeking a solution to the problem of a lack of a gender-neutral pronoun in English that satisfies all needs, people since the mid-nineteenth century have proposed many new gender-neutral singular pronouns.[13] For example, sie, Spivak pronouns, and others. None of these new words (neologisms) have become standard use or adopted into books of English grammar. However, some sets of these neologistic pronouns have seen a use for real people with nonbinary gender identities, and for characters in fiction. These neologisms are the main topic explored in the list that follows in this article.

The list[edit | edit source]

This list is of third-person gender-neutral singular pronouns in English. Some are "new" pronouns, and others have been in use for over a hundred years.

Please feel free to add more, though note that if you don't provide citations for notability or include all five forms your entry may be moved to the talk page or be removed entirely. List pronoun sets in alphabetical order by their nominative form, or by the name of the set.

Alternating pronouns[edit | edit source]

he, her, his, herself (for one of many possible examples). Instead of using an alternative or neutral pronoun set, some people prefer an alternation between different sets. This is also called "rolling pronouns" by some.[14] Justice Ginsburg was in favor of alternating "he" and "she" pronouns to make legal documents gender-inclusive.[3]

Use in fiction: In K. A. Cook's short story "Blue Paint, Chocolate and Other Similes," in Crooked Words, most of the story involves the narrator Ben moving from one set of pronouns to another for Chris as he tries to figure out Chris's gender. When the narrator is trying to determine whether Chris is male or female, Ben alternates between thinking of Chris as he or she. Upon recognizing that Chris identifies as nonbinary, the narrator begins using ze pronouns for Chris. Then, Ben finally finds a good moment to ask for Chris's pronoun preference.[15]

Use by people: In the 2018 Gender Census, 13.8% of respondents chose "mix it up" both alone and in addition to other pronoun choices.[1] Nonbinary artist and activist Sasha Alexander uses alternating "she/they/he" pronouns,[16][17] as does author Pat Schmatz.[18]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell her a joke he laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet her I hug him.

- Pronominal possessive: When he does not get a haircut, her hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If my mobile phone runs out of power, he lets me borrow hers.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds herself. or Each child feeds himself.

E[edit | edit source]

There are several very similar sets of pronouns with the nominative form of "E," which have been independently proposed or revived over the last hundred years.[19][20]

E (Spivak pronouns)[edit | edit source]

E, Em, Eir, Eirs, Emself. These are sometimes called spivak pronouns. In 1990, Michael Spivak used them in his manual, The Joy of TeX, so that no person in his examples had a specified gender. These pronouns became well-known on the Internet because they were built into a popular multi-user chat, LambdaMOO, in 1991. Many users enjoyed choosing pronouns that didn't specify their gender. The pronouns then became a common feature of other multi-user chats made throughout the 1990s. Although many other variations have been attributed to Michael Spivak, this is the actual set Spivak used in The Joy of TeX in 1990 or 1991. Note that he always capitalized all forms of it, but not all users of these pronouns do so. [21] Spivak doesn't indicate whether he created these pronouns, or adopted or adapted them from somewhere else. Spivak is credited with having created these pronouns, although his book doesn't outright say that they're of his own creation. (Compare Elverson's ey pronouns, which are very similar, with only a small spelling difference in the nominative form.)

Use in real life and non-fiction:

- When a programmer added this pronoun set to LambdaMOO in 1991, he used the same spelling as Spivak, but not capitalized.[22] Regarding LambdaMOO, John Costello wrote, "I know the wizard who originally included the spivak pronouns on the MOO. He says he did it just on a whim after having read the Joy of TeX — he never thought they'd acquire the sexual and political nimbus they have over the years."[21] LambdaMOO's "help spivak" command explains that these pronouns "were developed by mathematician Michael Spivak for use in his books."[23] Programmer Roger "Rog" Crew tested the LambdaMOO system by putting more pronoun options into it in May 1991, including Spivak's set he remembered from The Joy of TeX. Crew didn't delete the pronouns after testing them, and later expressed "dismay" that the spivak pronouns became popular.[24][25]

- Spivak pronouns became such a part of 1990s Internet culture that a handbook to that culture, Yib's Guide to Mooing (2003), uses spivak pronouns whenever speaking of a hypothetical person whose gender need not be specified.[26]

- In Internet environments, spivak was categorized not only as a set of pronouns but as a gender identity, which Thomas describes: "The spivak gender [...] is more representative of an emotional and intellectual state than of a physical configuration. It should be pointed out at the start that the sexuality available to a spivak is a bonus of online life, but it isn't the raison d'etre. Rather, it's a subtle notion of a gender-free condition. It's not androgynous. It's not unisexual. It's simply ambiguous."[27] Some self-described spivaks use spivak as a proper noun for their non-binary gender identity.

Use in fiction:

- Steven Shaviro's theoretical fiction novel Doom Patrols (1995-1997) uses spivak pronouns at times.[28]

- The English translation of Sayuri Ueda's science fiction novel The Cage of Zeus (2011) uses spivak pronouns for genetically engineered characters with non-dyadic bodies and non-binary gender.[29]

- In Orion's Arm (a fictional 12th millennium AD setting, as non-specific pronouns for sophonts of any gender, including AIs and aliens.[30]

Use for people:

- In 1996, 74 out of 7064 users on LambdaMOO went by spivak pronouns, making it the second most popular nonbinary pronoun there.[31] In 2002, 108 out of 4061 users on LambdaMOO used spivak pronouns, making it the most popular neologistic pronoun set there.[21]

- In 1996, 10 out of 1015 users on MediaMOO went by spivak pronouns, making these the second most popular nonbinary pronoun.[32]

- The comic artist Maia Kobabe and the author Bogi "prezzey" Takács go by spivak pronouns.[33]

- In the 2019 Gender Census, 5.2% of participants were happy for people to use Spivak pronouns when referring to them.[1]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke E laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug Em.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, Eir hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow Eirs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds Emself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170721055627/http://pronoun.is/e

Ey (Elverson pronouns)[edit | edit source]

ey, em, eir, eirs, emself. (Compare the spivak pronoun E, which is very similar, with only a small spelling difference in the nominative form.) Called the Elverson pronouns, these were "created by Christine M. Elverson of Skokie, Illinois, to win a contest in 1975. (Black, Judie, ‘Ey has a word for it’, 1975-08-23.). Promoted as preferable to other major contenders (sie, zie and singular ‘they’) by John Williams's Gender-neutral Pronoun FAQ (2004)."[34]

Use in real life and non-fiction:

- The Elverson pronouns were used by Eric Klein in the Laws of Oceania, 1993, to be gender-inclusive in a nonfictional micronation. Sometimes this pronoun set is mistakenly called "spivak pronouns," which differ only in the nominative form.

- In the 2019 Gender Census, about 0.1% of participants were happy for people to use Elverson pronouns when referring to them.[1]

Use in fiction:

- CJ Carter's science fiction novel, Que Será Serees (2011) is about a species of people with a single-gender, who are all called by Elverson's "ey" pronouns. Carter encourages other authors to use these gender-neutral pronouns.[35][36]

- In K. A. Cook's short story "Misstery Man," the self-described non-binary character Darcy asks to be called by "ey and eir" pronouns.[37]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke ey laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug em.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, eir hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow eirs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds emself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170717021620/http://pronoun.is/ey

Fae[edit | edit source]

fae, faer, faer, faers, faerself. A fairy (faery, faerie, fey or Fair Folk) themed set created no later than 2013.[38] This was the most commonly used nounself pronoun set in 2021.[39]

Variations:

- Fae, vaer, vaers, vaerself was created by Shade (Tumblr user shadaras) in 2013.[40]

- Fey, fey, feys, feys, feyself was recorded in 2014,[41] of unknown origin.

Controversy:

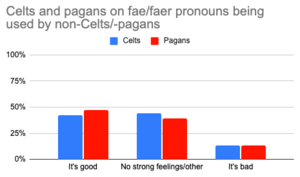

- In 2020 a couple of TikToks claiming that fae/faer pronouns are cultural appropriation went viral. Since then, it's not uncommon for people to repeat this claim in defence of either pagans, Celtic cultures and their descendents, or both. However, this claim seems groundless, as Celtic cultures do not generally call fairies "Fae" (it's a French word), and Paganism is too broad and faith-inclusive for any such practice to be considered appropriative. In Twitter polls, only a minority of about 13% from each culture felt that use of these pronouns by outsiders was bad, compared to over 40% from each culture feeling positively.[38]

Usage:

- In the 2019 Gender Census, 4.3% of participants were happy for people to use fae pronouns when referring to them[1]. "Fae" was the only nounself pronoun with a comparable level of popularity in that survey.

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke fae laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug faer.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, faer hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If my mobile phone runs out of power, fae lets me borrow faers.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds faerself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20180902190005/http://pronoun.is/fae/faer/faer/faers/faerself

Female pronouns[edit | edit source]

See She.

He[edit | edit source]

he, him, his, his, himself. Often called male pronouns, grammarians acknowledge that this standard set of pronouns can also be used as gender-neutral or gender-inclusive pronouns for unspecified persons, such as in instructions and legal documents. In the eighteenth century, when prescriptive grammarians decided that "singular they" was no longer acceptable as a gender-neutral pronoun, they instead recommended, "gender-neutral he." "Prescriptive grammarians have been calling for 'he' as the gender-neutral pronoun of choice since at least 1745, when a British schoolmistress named Anne Fisher laid down the law in A New Grammar."[3] The use of "gender-neutral he" can make problems in how laws are interpreted, because it's unclear whether it is meant to be gender-inclusive or male-only. For example, in 1927, "the Canadian Supreme Court ruled that women were not persons because its statutes referred to 'persons' with male pronouns."[42][4] In the USA in the nineteenth century, suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton fought for laws to stop using the "gender-neutral he," because there were cases where this pronoun had been arbitrarily interpreted as a "male he" in order to exclude women from legal protections, or from the right to a license that they had passed exams for. This abuse of legal language happened even in if the documents explicitly said that "he" was meant to include women.[3] Thanks to the work in the 1970s by feminists Casey Miller and Kate Swift, "gender-neutral he" has been significantly phased out of use, replaced by he or she.[43]

Use for real non-binary people: There are non-binary people who ask to be called by "he" pronouns, such as writer Richard O'Brien, autobiographer Jennie June, and guitarist Pete Townshend.

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke he laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug him.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, his hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow his.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds himself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170729140747/http://pronoun.is/he

Usage:

- In the 2019 Gender Census survey, 30.8% of participants were happy for people to use he pronouns when referring to them.[1]

He or she[edit | edit source]

See also: alternating pronouns

he or she, him or her, his or her, his or hers, himself or herself. These are very commonly used as gender-neutral pronouns for unspecified persons, such as in instructions and legal documents. Although grammatically acceptable, and a step more inclusive than only using "he" in these contexts, its length soon makes it cumbersome.[44] It almost always puts the "male" pronoun before the "female" pronoun, which is a little less than equality. (Similar efforts at inclusive language almost always end up with this same male-first ordering: "the habit of always saying 'male and female,' 'husbands and wives,' 'men and women' revealed an unquestioned priority," as pointed out by Casey Miller and Kate Swift in Words and Women (1976),[45] a book on sexism in language and feminist efforts for inclusive language.) "He or she" also gives the impression of including binary genders, while excluding the possibility of other genders.

Use by nonbinary people: Interestingly enough, although "he or she" may be the most popularly used inclusive pronoun set (along with "they"), and therefore may seem an obvious choice for nonbinary people, this set doesn't seem to be popularly used by nonbinary people. However, this may be an artifact of the way the surveys were taken. The 2018 Gender Census found 13.8% of the respondents asked people to "mix up" their pronouns (alternating pronouns).[1] A 2012 survey found 20 respondents who wished to be called both "he" and "she."[46] It may be the case that people who prefer to be called "he or she" simply entered their preference into the surveys in a slightly different format. It may also be the case that it's virtually unheard-of for nonbinary people to feel that "he or she" represents them. Either way, its absence in these surveys is intriguing and may need to be addressed more specifically in future surveys.

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke he or she laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug him or her.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, his or her hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow his or hers.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds himself or herself.

Hu[edit | edit source]

Hu, hum, hus, humself (or hu, hum, hus, huself). These singular neutral pronouns were originally coined by Sasha Newborn in 1982. She called the neologisms Humanist as they are nounself pronouns based on the word (noun) human, which is also how they're pronounced. While this pronoun set has not been widely used, a variation (hu, hu) did gain some attention in the 2024 US presidential election, where one candidate offered hu/hu as a pronoun option in a campaign form.[47]

Use by nonbinary people: A variation where hum is pronounced like the existing word hum, rather than like hew, has gained some traction.

Forms:

- Nominative: Hu loves hiking and climbing.

- Accusative: I have no idea what they said to hum.

- Pronominal possessive: It's hard to believe someone stole hus car.

- Predicative possessive: It's easy to believe the car is hus.

- Reflexive: Each of us needs to consider this humself.

On Fandom: https://pronoun.fandom.com/wiki/Humanself

On Pronouns: https://en.pronouns.page/hu

On Pronouns List: https://pronounslist.com/hum-hum

On Universal English: https://universalenglish.org/gender-neutral-english-pronouns/

It[edit | edit source]

it, it, its, its, itself. This standard English set of genderless pronouns is used for inanimate objects, animals, and human infants. During Dickens’ time, these were also acceptable pronouns for older human children and spirits of the dead, as these permutations of humanity were seen as not really male or female. This pronoun is not male or female. Using it for an adult human is often seen as an insult, dehumanizing. While considered offensive by most, some nonbinary people use "it" as a means of reclamation and to challenge the idea that genderlessness is inherently dehumanizing.

Because "it" pronouns are the default on LamdaMOO and on similar multi-user environments, they tend to be common there, but less common than "he" or "she." In 1996, "it" pronouns were the most popular non-binary pronoun choice on LambdaMOO (1162 out of 7065 player characters) and MediaMOO (280 out of 1015 player characters).[48]

Use for real nonbinary people: In the 2019 Gender Census, 4.4% of the participants were happy for people to use it pronouns when referring to them.[1] Notable nonbinary people who accept being called by it pronouns include the Venezuelan singer Arca (b. 1989).[49]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke it laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug it.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, its hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow its.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds itself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170810062945/http://pronoun.is/it

Male pronouns[edit | edit source]

See he.

Name[edit | edit source]

See no pronouns or nounself pronouns.

Ne[edit | edit source]

Several sets of pronouns use "ne" in the nominative form. One set of "ne" pronouns is one of the oldest sets of neo-pronouns, but not all its forms were recorded: ne, nim, nis, (not recorded), (not recorded), which was created around 1850,[19] and appeared in print in 1884.[20] Some of the better-attested sets of "ne" pronouns, in alphabetical order:

Ne (nem)[edit | edit source]

ne, nem, nir, nirs, nemself. In the 2019 Gender Census, 27 participants (0.2%) entered the set of pronouns ne/nem/nir/nirs/nemself.[1]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke ne laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug nem.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, nir hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow nirs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds nemself.

Ne (ner)[edit | edit source]

ne, ner, nis, nis, nemself. In a 1974 issue of Today's Education, "Mildred Fenner attributes this to Fred Wilhelms."[20][19] Veterinarian Al Lippart independently proposed the same set of pronouns in 1999, recommending them for use when it would be inappropriate to specify the gender of a human, animal, or deity.[50] Lawyer Roberta Morris also independently proposed this same set of pronouns in 2009, saying that these pronouns would be more efficient for within the 140 character limit of Twitter than "he or she." Morris also pointed out that the "n" can refer to "neuter."[51]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke ne laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug ner.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, nis hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow nis.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds nemself.

No pronouns[edit | edit source]

Many nonbinary people prefer not to be referred to by pronouns of any kind; see below for statistics. This can be because they have learned that any set of pronouns can potentially feel uncomfortable for them (gender dysphoria). In fiction and other writing, avoiding the use of any pronouns for a person can be used to avoid giving any sign of that person's gender. Instead of using pronouns, a person can be referred to by a name, a descriptive word, or the sentence can be rephrased.

While the grammatical labels on the sample sentences below are no longer correct, the sentences can be adjusted to exclude pronouns while still talking about a specific person.

- Nominative: (Demonstrative + noun replaces pronoun) When I tell someone a joke, that person laughs.

- Accusative: (Eliminated second reference to the person) I greet my friend with a hug.

- Pronominal possessive: (Replaced with an "it" that technically has no antecedent but clearly refers to the possessed thing) When someone does not get a haircut, it grows long.

- Predicative possessive: (Possessive eliminated) If my mobile phone runs out of power, my friend lends me another.

- Reflexive: (Reflexive emphasizing independence replaced with adverb) Each child gets food independently.

Using names or descriptions without changing the sentence structure:

- Nominative: When I tell Taylor a joke Taylor laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet Ash I hug Ash.

- Pronominal possessive: When the kid does not get a haircut, the kid's hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow the friend's.

- Reflexive: Morgan feeds Morgan.

Other noteworthy techniques for removing third-person pronouns from a sentence include:

- Passive voice: "Taylor's mopping the kitchen. When he finishes, we'll go for a walk" becomes "Taylor's mopping the kitchen. When it's done, we'll go for a walk." Here "it" refers to the kitchen or maybe the task of mopping, and we use the passive voice because there's no need to repeat who's doing it.

- Second person: Instead of talking about someone in the third person, why not talk to them instead? Say you're talking to Kevin and Elisa, who prefers no third-person pronouns, is in the room. You could tell Kevin, "I'd love to go with you for coffee, but Elisa's already claimed me for the evening," but if you do that and want to start expanding on what Elisa's up to, you might be tempted to use third-person pronouns. Instead, you could shift to Elisa and say "but you've got me booked for the evening," and then Elisa could tell about the plans without being spoken for.

- Substitute an article for a possessive pronoun: "Morgan couldn't find his coat" becomes "Morgan couldn't find the coat." "Ash broke her toe" becomes "Ash broke a toe."

- Other ways to rephrase. "The alien slithered closer, and its eyes glowed" becomes "The alien slithered closer, eyes glowing."

In use for real nonbinary people: In the 2018 Gender Census, 10.1% of participants were happy for people to avoid using pronouns when referring to them.[1]

One[edit | edit source]

one, one, ones, one’s, oneself. This is a standard English set of pronouns used for a hypothetical person whose gender is not specified.

Usage:

- In the 2019 Gender Census, only 8 (0.1%) participants were happy for people to use the pronoun one when referring to them.[1]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke one laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug one.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, one's hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow one's.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds oneself.

Per[edit | edit source]

per (person), per, per, pers, perself. Called "person pronouns," these are meant to be used for a person of any gender. Compare Phelps's phe pronouns, which are also based on the word "person." John Clark created "per" pronouns in a 1972 issue of the Newsletter of the American Anthropological Association.[20]

Use in fiction: In Marge Piercy's feminist novel, Woman on the Edge of Time, 1976, Piercy used "per" pronouns for all citizens of a utopian future in which gender was no longer seen as a big difference between people.[21]

Use in real life and non-fiction: Person pronouns were one of the sets of pronouns built into MediaMOO for users to choose from.[52] Richard Ekins and Dave King used these pronouns in the book The Transgender Phenomenon (2006).[53] Activist Christie Elan-Cane uses these pronouns for perself. In the 2019 Gender Census, only 6 (0.1%) participants were happy for people to use the pronoun per when referring to them.[1]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke per laughs. (Or person laughs.)

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug per.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, per hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow pers.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds perself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170711180841/http://pronoun.is/per

She[edit | edit source]

she, her, her, hers, herself. Often called female pronouns, although, in standard usage, they're not used exclusively for women. Grammarians agree that it is standard and acceptable for this set to be used for women, female animals, and ships. The set is also poetically used for countries and fields of studies, which grammarians also see as acceptable. Some feminists recommend replacing "gender-neutral he" with "gender-neutral she." "In 1970, Dana Densmore’s article “Speech is the Form of Thought” appeared in No More Fun and Games: A Journal of Female Liberation; Densmore is evidently the first U.S. advocate of 'she' as a gender-neutral pronoun, a solution many writers, particularly academic writers, favor today."[3] In 1974, Gena Corea recommended replacing the "gender-neutral he" with a "gender-neutral she," and like Denmore, argued that the word "she" would be understood to include the word "he."[20]

Use as a gender-neutral pronoun in fiction:

- Anne Leckie's science fiction novels Ancillary Justice (2013) and Ancillary Sword (2014) were set in a futuristic society that is indifferent to gender, so all the characters are called by gender-neutral "she" pronouns, leaving their actual gender and sex undisclosed. Leckie says she had an assumption at the time that gender is binary, so these are likely not non-binary characters.[55]

- Cartoonist Rebecca Sugar explained that in her animated science fiction series, Steven Universe, the alien people called Gems really have no sex or gender, even though they all look like women. For this reason, the Gems are only arbitrarily called by "she" pronouns. Sugar said, "Technically, there are no female Gems! There are only Gems! [...] Why not look like human females? That's just what Gems happen to look like! [...] There's a 50 50 chance to use some pronoun on Earth, so why not feminine ones-- it's as convenient as it is arbitrary!"[56] This is a gender-neutral use of "she" pronouns.

Use by real nonbinary people: There are nonbinary people who ask people to use "she" pronouns for them, such as singer-songwriter Elly Jackson[citation needed], musician JD Samson, American comedian, writer, and nurse Kelli Dunham,[57] British musician Du Blonde,[58] poet jayy dodd,[59][60] author and public speaker Olave Basabose,[61] actor Cara Delevingne, activist Chao Xiaomi,[62] and rapper Angel Haze.[54] In the 2018 Gender Census, 29% of participants were happy for people to use she pronouns when referring to them.[1]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke she laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug her.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, her hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow hers.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds herself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170730145111/http://pronoun.is/she

S/he[edit | edit source]

s/he (sHe), hir, hir, hirs, hirself. A set of English gender-neutral pronouns used in books by Timothy Leary in the 1970s, and then by counterculture writers influenced by Leary. For example, in Robert Anton Wilson's book Prometheus Rising (first published in 1983), which is strongly based on Leary's writings about consciousness, Wilson uses SHe [sic] pronouns to include humans of any kind, as short for "she or he."[63] It was used in non-fiction writings about spirituality by the Elf Queen's Daughters and the Silver Elves from the 1970s to the present 2010s. It was also used in fiction in Peter David's Star Trek books. Sometimes with mixed caps, as shown. This pronoun was not entered in the 2018 Gender Census.[1] However, notable nonbinary people who have asked to be called by s/he pronouns include revolutionary communist Leslie Feinberg. In hir book Trans Liberation: Beyond Pink or Blue, Feinberg wrote,

"I asked Beacon Press to use s/he [sic] in the author description of me on the cover of Transgender Warriors [another book by Feinberg]. That pronoun is a contribution from the women's liberation movement. Prior to that struggle, the pronoun 'he' was almost universally used to describe humankind-- 'mankind.' So s/he' opened up the pronoun to include 'womankind.' I used s/he on my book jacket because it is recognizable as a gender-neutral pronoun to people. But I personally prefer the pronoun ze because, for me, it melds mankind and womankind into humankind."[64]

At different times, Feinberg has asked to go by "s/he," "ze," or "she" pronouns depending on hir needs and the message meant to send. As quoted in hir obituary, Feinberg had said, "I care which pronoun is used, but people have been respectful to me with the wrong pronoun and disrespectful with the right one. It matters whether someone is using the pronoun as a bigot, or if they are trying to demonstrate respect."[65]. Another notable nonbinary person, singer-songwriter Genesis Breyer P-orridge asks to be referred to by a different version of the s/he pronouns: s/he, h/er, h/er, h/ers, h/erself.[66] The Taiwanese intersex activist Hiker Chiu goes by another variation: s/he, her/him.[67]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke s/he laughs. (Or sHe laughs. Or s/He laughs.)

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug hir.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, hir hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow hirs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds hirself.

Sie[edit | edit source]

sie, hir, hir, hirs, hirself. Pronounced like either "she" and "her," or "see" and "hear." Derived from German pronouns for "she" and "they."[68] Since the early 1990s, this set has been widely used on the Internet for gender-neutral language when speaking of no specific person, for nonbinary gender characters, and by nonbinary gender people themselves. Elizabeth Bear used these pronouns in a fantasy novel, Dust.[69] Notable real people who go by sie/hir include the American autistic activist Mel Baggs (1980 - 2020)[70]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke sie laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug hir.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, hir hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow hirs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds hirself.

Sne[edit | edit source]

sne, fe, se, se's, sneself. An uncommon set of pronouns first attested in anonymous online discussions in the late 2010s. The paradigm consists of nominative sne, accusative fe, possessive se, and reflexive sneself (sometimes rendered sneedself). Its structure parallels other neopronoun sets.

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke sne laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug fe.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, se hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow se's.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds sneself (or sneedself).

They[edit | edit source]

There is more information about this topic here: singular they

Thon[edit | edit source]

thon, thon, thons, thon's, thonself. American composer Charles Crozat Converse of Erie, Pennsylvania proposed this pronoun in 1858, based on a contraction of "that one."[71] The Gender-Neutral Pronoun FAQ gives this pronoun's date of origin as 1884 instead,[19] while Words and Women gives 1859.[72] The "thon" pronoun was included in some dictionaries: Webster's International Dictionary (1910), and Funk & Wagnalls New Standard Dictionary (1913), and Webster's Second International (1959). Funk & Wagnalls offered these sentences to show how it should be used: "If Harry or his wife comes, I will be on hand to greet thon," and "Each pupil must learn thon's lesson." "Thon" was used throughout the writings by the founders of chiropractic, B.J. and D.D. Palmer, in 1910.[71] "Thon" is therefore familiar to chiropractors, and sometimes still appears in chiropractic writings, and in works by people who were influenced by that field.

Use for real nonbinary people: In the 2019 Gender Census, 18 (0.2%) people said that they were happy for people to use thon to refer to them.[1]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke thon laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug thon.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, thons hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow thon's.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds thonself.

On Pronoun Island: [ https://web.archive.org/web/20190909212705/http://pronoun.is/thon ]

Ve[edit | edit source]

There are several sets of pronouns that use "ve" in the nominative form, the earliest of which was created in 1970.[73] In the 2019 Gender Census, 24 participants (0.2%) used a set of pronouns starting with ve.[1]

ve, ver, vis, vis, verself is the exact set used by Egan, Hulme, and Reynolds (see below). The set's date of creation and creator are not yet known to the editors of this wiki. A nearly-identical but incompletely recorded set was ve, vir, vis, (not recorded), (not recorded), which was created in 1970, and published in the May issue of Everywoman.[19][20]

Use in fiction:

- In Keri Hulme's mystery novel The Bone People (1984), a character is called by these ve pronouns.[74]

- Used by Greg Egan for non-binary gender characters-- including artificial intelligence, as well as transgender humans who identify as a specific nonbinary gender they call "asex"-- in his novels Distress (1995) and Diaspora (1998).[75] Egan is sometimes credited with having created these pronouns, but it doesn't appear that he claims to have done so.

- In Alastair Reynolds's science fiction novel On the Steel Breeze (2013) one character is called by these ve pronouns. The novel never gives any exposition about this character's sex, gender, or pronouns, and vis gender-neutrality doesn't influence the plot. The lack of remark gives the impression that a nonbinary gender is unremarkable, but this is also why some readers thought the pronouns were a misprint.[74]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke ve laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug ver. (Or: "I hug vir.)

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, vis hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow vis.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds verself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170619065210/http://pronoun.is/ve

Xe[edit | edit source]

There are several similar sets of neologistic gender-neutral pronouns that use "xe," "ze," "zhe," or "zie" in nominative form. Regardless of spelling, their nominative form is pronounced "zee," and was based on the pronoun sie. The earliest documented version was created in 1972.[20] In alphabetical order, some of the more common versions of this pronoun set include:

Xe, hir[edit | edit source]

xe, hir, hir, hirs, hirself. Compare the similar "ze, hir..." set, which is apparently used in more literature and by more people. The "xe" version was "Used on alt.support.intergendered and alt.support.crossdressing," transgender communities on the Internet in the 1990s.[76]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke xe laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug hir.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, hir hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow hirs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds hirself.

Xe, xir[edit | edit source]

xe, xir, xir, xirs, xirself. This pronoun set saw some use on the Internet at least as early as 1998.[77]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke xe laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug xir.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, xir hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow xirs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds xirself.

Xe, xyr (xem)[edit | edit source]

xe, xyr (xem), xyr, xyrs, xyrself (xemself). This pronoun set makes its earliest known appearance in 1993 in a conversation in an autism mailing list on the Internet.[78][79] The "xem" version of this pronoun set appears in a printed discussion from the mailing list of Autism Network International in 2000, with the explanation that it "was originally used to refer to an intersexed person, but is also used to refer to a person of any gender."[80] This pronoun set was recommended in 2005 by Jonathan de Boyne Pollard, with the version that includes "xem," and both "xyrself" and "xemself."[81]

Use for real nonbinary people: In the 2019 Gender Census, 7.2% of people said they'd be happy for people to use xe/xem/xyr/xyrs/xemself to refer to them.[1]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke xe laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug xem. (Or hug xyr.)

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, xyr hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow xyrs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds xyrself. (Or feeds xemself.)

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170731193720/http://pronoun.is/xe

Ze[edit | edit source]

There are several similar sets of neologistic gender-neutral pronouns that use "xe," "ze," "zhe," or "zie" in nominative form. Regardless of spelling, their nominative form is pronounced "zee," and was based on the pronoun sie. The earliest documented version was created in 1972.[20] "Ze, hir" is the best-attested of the "ze" pronoun sets; see the Talk page for other sets with this nominative form.

Ze, hir[edit | edit source]

ze, hir, hir, hirs, hirself. Compare the similar "xe, hir..." set, which is the version less attested by print sources. Sarah Dopp wrote a blog post about the "ze" version in 2006.[82] Leslie Feinberg also used the "ze" version in the book Drag King Dreams (2006),[83] Erika Lopez used the "ze" version in The Girl Must Die: A Monster Girl Memoir (2010).[84] M. J. Locke used the "ze" version in the book Up Against It (2011).[85]

Use in fiction:

- Kameron Hurley used these pronouns in the fantasy novels The Mirror Empire and Empire Ascendant, for characters who are ataisa, an in-between gender role where their culture puts everyone who has a nonbinary gender.[86]

- In Seth Dickinson's short science fiction story, "Sekhmet Hunts the Dying Gnosis: A Computation" (2014), a transhuman character of "uncertain ... sex" is called by the pronoun "ze," which only appears in the nominative form.[87]

- In K. A. Cook's short story "Blue Paint, Chocolate and Other Similes," in Crooked Words, when the narrator Ben recognizes that Chris identifies as nonbinary, Ben begins using "ze, hir" pronouns for Chris, before finding a good moment to ask for Chris's actual pronoun preference.[88] In another story by K. A. Cook, "The Differently Animated and Queer Society," the character Pat goes by "ze, hir" pronouns, and uses them for other characters before finding out each of their own pronoun preferences.[89]

Use for real people:

- Kate Bornstein used them in the books Nearly Roadkill (1996) (with Caitlin Sullivan June)[90], and My Gender Workbook (1998) in reference to hirself, and to other specific transgender people, as well as hypothetical persons of unspecified gender.[91] Today, Bornstein goes by any pronouns.[92][93]

- Leslie Feinberg asked to be called by "ze, hir" pronouns, along with "zie, hir" and "she."[94] In a magazine interview from 2014, Gabriel Antonio and another anonymous person both asked to be called by these pronouns.[95]

- Writer Sassafras Lowrey uses ze/hir pronouns.[96]

- In the 2019 Gender Census, 4.7% of participants said they would be happy for people to use "ze/hir/hir/hirs/hirself" to refer to them.[1]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke ze laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug hir.

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, hir hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow hirs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds hirself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170523031355/http://pronoun.is/ze

Zie[edit | edit source]

zie, zir (zim), zir, zirs, zirself. (Compare the most similar pronoun set, "ze, zir", and other similar pronouns, "xe" and "zhe".) The Gender-Neutral Pronoun FAQ says this set (with the "zie" spelling, and accusative "zir") was widely used on the Internet at the time but doesn't know when it was created.[97] Andrés Pérez-Bergquist recommended a version of this set (with the "zie" spelling, and accusative "zim") in 2000, but claims not to have created it.[98]

Use in fiction:

- This set (with the "zie" spelling, and accusative "zir") is in the fantasy setting of Bard Bloom's World Tree, for the many characters with sexes other than female or male. Many species in this setting have such sexes, including the protagonist of a book in that setting, Sythyry's Journal, which was first serialized as a blog starting in 2002. The setting also has a role-playing game handbook, World Tree: A roleplaying game of species and civilization (2001).

Use for real nonbinary people: In the 2019 Gender Census, 11 people (around 0.1%) said they'd be happy for people to use zie/zir (or some similar spelling) to refer to them.[1] A notable nonbinary person who goes by ze/zim is the American writer and model Devin-Norelle.[99][100]

Forms:

- Nominative: When I tell someone a joke zie laughs.

- Accusative: When I greet a friend I hug zir. (Or hug zim.)

- Pronominal possessive: When someone does not get a haircut, zir hair grows long.

- Predicative possessive: If I need a phone, my friend lets me borrow zirs.

- Reflexive: Each child feeds zirself.

On Pronoun Island: https://web.archive.org/web/20170719212704/http://pronoun.is/zie

See also[edit | edit source]

| See also a blog post about this topic on our Tumblr. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 Gender Census 2019 - The Full Report (Worldwide), April 2019. Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Churchyard, Henry. "Jane Austen and other famous authors violate what everyone learned in their English class". Archived from the original on 19 March 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Bustillos, Maria (6 January 2011). "Our Desperate, 250-Year-Long Search for a Gender-Neutral Pronoun". The Awl. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Pullum, Geoffrey (18 August 2004). "Canada Supreme Court Gets the Grammar Right". Language Log. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023.

- ↑ Baron, Dennis (1986). Grammar and Gender. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03526-8. as cited by Williams, John (1990s).

- ↑ Williams, John. "History - Native-English GNPs". Gender-Neutral Pronoun FAQ. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010.

- ↑ "Epicene pronouns". American Heritage Book of English Usage. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ↑ K. A. Cook, "The Differently Animated and Queer Society." Crooked Words. Unpaged.

- ↑ Rebecca Hersher, "'Yo' said what?" April 24, 2013. NPR: Code Switch. [1] Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Elizabeth J. Elrod, "Give us a gender neutral pronoun, yo!: The need for and creation of a gender neutral, singular, third person, personal pronoun." Undergraduate Honors Theses paper 200. 2014. http://dc.etsu.edu/honors/200 or http://dc.etsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1203&context=honors (PDF)

- ↑ Graham, Lore (28 September 2015). "UNPOPULAR OPINION: We Should Have More Pronouns". Archived from the original on 3 September 2018.

- ↑ https://lgbta.fandom.com/wiki/Neopronouns#It Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "History". Gender-Neutral Pronoun FAQ. Archived from the original on 7 February 2005.

- ↑ Jakubowski, Kaylee (4 March 2014). "Too Queer for Your Binary: Everything You Need to Know and More About Non-Binary Identities". Everyday Feminism. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

rolling pronouns (which involves changing the persons pronoun each time that one comes up in a sentence – for example, “She went to the store, and on the way there he ran into an old friend who asked hir how they were doing”)

- ↑ K. A. Cook, "Blue Paint, Chocolate and Other Similes." Crooked Words. Unpaged.

- ↑ @BlackTransMedia (19 August 2019). "What a #blacktranseverything thread thank you sis[...] I don't post photos of myself here yall inspire(d) me so here I go.. I'm sasha founder/one of the co-directors of black trans media, I use she/they/he pronouns + insist that you mix it up or use my name #blacktransloveiswealth" – via Twitter.

- ↑ Wicker, Randolfe (9 March 2015). "TRANS POET SASHA - SHE, HE, THEY". YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ↑ "Gender Stories: Writing non-binary". 30 June 2019. Archived from the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2020.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 4.2.5. Comprehensive Listing of Neologisms, March 10 2007

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 Baron, Dennis. "The Words that Failed: A chronology of early nonbinary pronouns". Archived from the original on 22 June 2017.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 https://web.archive.org/web/20070310125817/http://aetherlumina.com/gnp/references.html

- ↑ V.Dentata (1999). "MOO Bash FAQ". Archived from the original on 8 March 2016.

- ↑ Sue Thomas, Hello World: Travels in Virtuality. 2004. P. 33.

- ↑ Sue Thomas, Hello World: Travels in Virtuality. p. 34.

- ↑ Steve Jones, Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting Computer-Mediated Community and Technology. p. 141.

- ↑ Elizabeth Hess, Yib's Guide to Mooing: Getting the Most from Virtual Communities on the Internet. 2003. p. 3, p. 283.

- ↑ Sue Thomas, Hello World: Travels in Virtuality. p. 31-32.

- ↑ Steven Shaviro, "Preface." Doom Patrols. http://www.dhalgren.com/Doom/ch00.html Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Sayuri Ueda, The Cage of Zeus. 2011.

- ↑ "Pronouns, Anglish". Orion's Arm Universe Project. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023.

- ↑ Steve Jones, Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting Computer-Mediated Community and Technology. p. 142.

- ↑ Steve Jones, Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting Computer-Mediated Community and Technology. p. 141.

- ↑ Bogi Takács' biography on Smashwords, captured March 2016. Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:List_of_protologisms_by_topic/third_person_singular_gender_neutral_pronouns#cite_note-1 Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ CJ Carter, "Genderless singular pronouns." http://tib.cjcs.com/genderless-pronouns-ey-em-and-eir-2/ Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "Que Será Serees". CJ's Creative Studio. http://cjcs.com/writing/fiction/que-sera-serees/ Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ K. A. Cook, "Misstery Man." Crooked Words. Unpaged.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 "On fae/faer pronouns and cultural appropriation". Gender Census Tumblr. 2021-02-20. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- ↑ "Gender Census 2021: Worldwide Report". Gender Census. 2021-04-01. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ "So I might possibly have spent today on and off prodding pronouns..." 1 October 2013. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023.

- ↑ Ask A Nonbinary's list of unthemed pronouns, captured March 2016 Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "Pronoun perspectives." Gender neutral pronoun blog. https://genderneutralpronoun.wordpress.com/links/pronoun-perspectives/ Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Isele, Elizabeth (Fall 1994). "Casey Miller and Kate Swift: Women Who Dared To Disturb the Lexicon". Women in Literature and Life Assembly. 3. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023.

- ↑ "GNP Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)". Archived from the original on 5 February 2005.

- ↑ Casey Miller and Kate Swift, Words and Women. Page x.

- ↑ anlamasanda, "Results of pronoun survey." January 1, 2012. http://anlamasanda.tumblr.com/post/15140114246 Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Valerie Richardson, "Hu/hu? Harris for President campaign presses job applicants to pick zir pronouns", Aug 15, 2024. Higher Ground Times.

- ↑ Steve Jones, Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting Computer-Mediated Community and Technology. p. 142.

- ↑ Fallon, Patric (8 November 2019). "Arca Is the Artist of the Decade". Vice. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ↑ Lippart, Al (1999). "Introducing the New Neutral Third Person Singular Personal Pronoun". Archived from the original on 18 March 2009.

- ↑ Roberta Morris, "The need for a neuter pronoun: A solution." September 29, 2009. http://myunpublishedworks2.blogspot.com/2009/09/need-for-neuter-pronoun-solution.html Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Laura Borràs Castanyer, ed. Textualidades electrónicas: Nuevos escenarios para la literatura. p. 158.

- ↑ Richard Ekins and Dave King. The Transgender Phenomenon. Sage Publications, 2006.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 @AngelHaze (2 May 2018). "No maam. still identify as agender but just for my own sanity, i like she/her" – via Twitter.

- ↑ Geek's Guide to the Galaxy, "Sci-fi's hottest new writer won't tell you the sex of her characters." October 11, 2014. Wired. http://www.wired.com/2014/10/geeks-guide-ann-leckie/ Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Rebecca Sugar. Reddit. http://www.reddit.com/user/RebeccaSugar Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "THE STORY". kellidunham.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ↑ Sept 27, 2019 instagram post Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Kelly, Devin (January 23, 2017). "Interview with jayy dodd, author of Mannish Tongues". entropymag.org. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ↑ Instagram bio, retrieved May 15 2020

- ↑ This is your annually scheduled PSA: My pronouns are she/her/hers., July 22, 2019 Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Fang, Nanlin; Luu, Chieu. "Chao Xiaomi leads China's fight for transgender rights". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ Robert Anton Wilson, Prometheus Rising. Second edition. Grand Junction, Colorado: Hilaritas Press, 2016. Page 55.

- ↑ Leslie Feinberg, Trans Liberation: Beyond Pink or Blue. Page 71.

- ↑ https://www.lesliefeinberg.net/self/ Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "Genesis Breyer P-orridge." http://www.genesisbreyerporridge.com/genesisbreyerporridge.com/Genesis_BREYER_P-ORRIDGE_Home.html Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Entenmann, Leah (21 December 2015). ""We Are Not Monsters. We Are Full of Love." — Hiker Chiu, Taiwan". Medium. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ↑ "GNP FAQ", archive Feb 29 2012

- ↑ All our worlds: Diverse fantastic fiction. http://doublediamond.net/aow Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "Transgender day of visibility". April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Barge, Fred (August 14, 1992). "Viewpoints from involvement -- 'thon'". Dynamic Chiropractic. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023.

- ↑ Casey Miller and Kate Swift, Words and Women. Page 130.

- ↑ https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28036096 (Everywoman, Vol 1, Issue 1, May 8, 1970. Page 2, middle of left side, under the heading "Manglish".) Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Outis, "gender-neutral characters and pronouns." November 20, 2013. https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/1580481-gender-neutral-characters-and-pronouns Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ John McIntosh, "ve, vis, ver." [2] Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "GNP FAQ." [3]

- ↑ Benton, "ADOM and sex." rec.games.roguelike.adom (newsgroup). May 18, 1998. https://groups.google.com/forum/#!msg/rec.games.roguelike.adom/6RBaViEF0gE/v33A7kKysiwJ Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Jim Sinclair, "Re: Jim and Steve's snoring discussion." September 14, 1993. bit.listserv.autism, Usenet. https://groups.google.com/forum/?fromgroups#!msg/bit.listserv.autism/2pyrOMzt_nQ/5J-RU5P3hnIJ Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "Xe." Wiktionary. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/xe Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ J. Blackburn, K. Gottschewski, Elsa George, and Niki L. "A discussion about Theory of Mind: From an Autistic Perspective," Proceedings of Autism Europe's 6th International Congress, Glasgow 19-21 May 2000, in print. https://web.archive.org/web/20060213070451/http://www.autistics.org/library/AE2000-ToM.html

- ↑ Jonathan de Boyne Pollard. "'Xe', 'xem', and 'xyr' are sex-neutral pronouns and adjectives." 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20071010095912/http://homepages.tesco.net/J.deBoynePollard/FGA/sex-neutral-pronouns.html

- ↑ Dopp, Sarah (13 August 2006). "How transgender folk are fixing an age-old literary problem". Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ↑ Leslie Feinberg, Drag King Dreams. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006.

- ↑ Erika Lopez, The Girl Must Die: A Monster Girl Memoir. Hicken, Jeffrey, San Francisco: Monster Girl Media, 2010.

- ↑ M. J. Locke, up Against It. New York: Tor, 2011.

- ↑ Hurley, Kameron (3 September 2014). "Beyond He-Man and She-Ra: Writing nonbinary characters". Archived from the original on 17 July 2023.

- ↑ Seth Dickinson, "Sekhmet Hunts the Dying Gnosis: A Computation." Beneath Ceaseless Skies, issue 143. March 20, 2014. http://www.beneath-ceaseless-skies.com/stories/sekhmet-hunts-the-dying-gnosis-a-computation/ Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ K. A. Cook, "Blue Paint, Chocolate and Other Similes." Crooked Words. Unpaged.

- ↑ K. A. Cook, "The Differently Animated and Queer Society." Crooked Words. Unpaged.

- ↑ Caitlin Sullivan June and Kate Bornstein. Nearly Roadkill: An Infobahn erotic adventure. New York: Serpent's Tail, 1996, p. 10.

- ↑ Kate Bornstein, My Gender Workbook. 1st ed. 1998, p. 106-107, 119, 130-131, 154, 248.

- ↑ @katebornstein (July 12, 2019). "Over 71 years, I've at one time or another insisted on every pronoun in the book. Finally settled in to it doesn't matter to me what pronouns people use for me—it tells me more about them than it could ever say about me. So thanks for asking, it's up to you" – via Twitter.

- ↑ Raymond, Gerard (July 11, 2018). "Interview: Kate Bornstein on Their Broadway Debut in Straight White Men". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ↑ Minnie Bruce Pratt (17 November 2014). "Transgender Pioneer and Stone Butch Blues Author Leslie Feinberg Has Died". The Advocate.

- ↑ Donato, Al (25 November 2014). "He And She, Ze And Xe: The Case For Gender-Neutral Pronouns". The Plaid Zebra. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ↑ Lowrey, Sassafras (8 November 2017). "A Guide To Non-binary Pronouns And Why They Matter". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ↑ "GNP FAQ". Archived from the original on 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Pérez-Bergquist, Andrés (2000). "Gender-neutral pronouns: The value of zie". Archived from the original on 16 February 2019.

- ↑ Instagram profile, accessed 29 July 2020 Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Michael Love Michael (9 September 2019). "Meet Devin-Norelle, Chromat's First Masculine of Center Model". PAPER. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2020.